Understanding Screenplay (part #2)

In the first post in this series we introduced the concept of the Screenplay pattern and busted a couple of popular myths about it. Now it's time to start digging into some code to give us a real example to demonstrate the pattern on.

The problem with writing this kind of tutorial, always, is finding the right balance between an example that's so complicated it gets in the way of your understanding the thing we're actually trying to learn about, and one that's so simplistic that the need for any kind of software design seems superfluous. If you'll forgive me, we'll err towards the simplistic here, and I'll trust that you've seen enough complex code in the wild to recognise the need for some design work.

Time for an example

Turn your imagination up to max and pretend we're building a web-based app that needs people to be able to sign up. This sign up feature is going to be the big differentiator to help us stand out in the market, I can feel it.

Sign-up is a two-step process, as described in this feature file:

Feature: Sign up

New accounts need to confirm their email to activate

their account.

Scenario: Successful sign-up

Given Tanya has created an account

When Tanya activates her account

Then Tanya should be authenticated

Scenario: Try to sign in without activating account

Given Bob has created an account

When Bob tries to sign in

Then Bob should not be authenticated

And Bob should see an error telling him to activate the account

So far so good. We have one happy path scenario for Tanya creating then activating her account, and being able to sign in. We have another that illustrates what happens if hapless Bob tries to sign in before he's got around to activating the account.

Now let's drop down a layer and have a look at the step definitions we've written that bring these scenarios to life our JavaScript project:

const { Given, When, Then } = require('cucumber')

const { assertThat, is, not, matchesPattern } = require('hamjest')

Given('{word} has created an account', function (name) {

this.createAccount({ name })

})

When('{word} tries to sign in', function (name) {

this.signIn({ name })

})

When('{word} activates his/her account', function (name) {

this.activateAccount({ name })

})

Then('{word} should not be authenticated', function (name) {

assertThat(this.isAuthenticated({ name }), is(not(true)))

})

Then('{word} should be authenticated', function (name) {

assertThat(this.isAuthenticated({ name }), is(true))

})

Then('{word} should see an error telling him/her to activate the account', function (name) {

assertThat(

this.authenticationError({ name }),

matchesPattern(/activate your account/)

)

})

There's a couple of things going on here, so let's pick them apart.

We can see that each step definition uses the cucumber expression syntax, avoiding the need for ugly regular expressions, and instead capturing the name of the user with the built in {word} parameter type. Partly, I just wanted to show off this new feature, but it's also going to come in handy later.

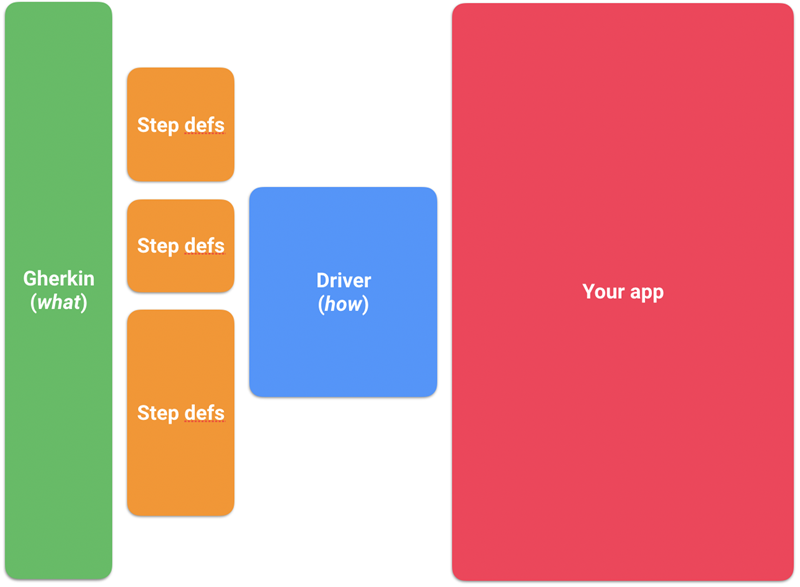

Next, notice that each of the step definition functions is a one-liner, delegating to a method on this. Delegating the automation work to helper methods allows us to keep a separation of concerns between these two layers:

- Step Definitions translate from plain English in the scenarios into code.

- Helper, or driver methods actually interact with the app.

Working this way, we build up a library of re-usable driver code that does the actual leg-work of automating our app. Gradually, we develop an API (some people even call it a DSL) for driving our application from our tests.

Introducing this separation also allows us the flexibility to swap in different implementations of the driver API, when we want to connect our automation at different layers of the app. If we want to, we can have a SeleniumDriver that uses a browser (perhaps via page objects), and a DomainDriver that does the same things directly against the domain model.

But I digress.

Where do the helper methods live?

In cucumber-js projects, this in the context of a step definition function is the World, an object that is created by Cucumber for the duration of the scenario, which we can add custom methods and properties to. Ruby's flavour of Cucumber offers the same concept. In Cucumber-JVM and SpecFlow projects you have to inject your own objects that contain your helpers, but the principle is the same.

We won't dig any deeper into our automation stack right now. Let's just trust that those helper methods are there, doing what they say they do.

A new requirement

As they tend to do from time to time, our product owner would like this app of ours to do something new. She has an idea that our app will have projects that users with existing accounts can create. I don't know where she gets these wild ideas.

Here's the feature file:

Feature: Create project

Users can create projects, only visible to themselves

Scenario: Create one project

Given Sue has signed up

When Sue creates a project

Then Sue should see the project

Scenario: Try to see someone else's project

Given Sue has signed up

And Bob has signed up

When Sue creates a project

Then Bob should not see any projects

We've introduced a handful of new steps here. Let's look at how these are defined:

const { Given, When, Then } = require('cucumber')

const { assertThat, is, not, matchesPattern, hasItem, isEmpty } = require('hamjest')

Given('{word} has created an account', function (name) {

this.createAccount({ name })

})

When('{word} tries to sign in', function (name) {

this.signIn({ name })

})

When('{word} activates his/her account', function (name) {

this.activateAccount({ name })

})

Given('{word} has signed up', function (name) {

this.createAccount({ name })

this.activateAccount({ name })

})

When('{word} (tries to )create(s) a project', function (name) {

this.createProject({ name, project: { name: 'a-project' }})

})

Then('{word} should see the project', function (name) {

assertThat(

this.getProjects({ name }),

hasItem({ name: 'a-project' })

)

})

Then('{word} should not see any projects', function (name) {

assertThat(

this.getProjects({ name }),

isEmpty()

)

})

Then('{word} should not be authenticated', function (name) {

assertThat(this.isAuthenticated({ name }), is(not(true)))

})

Then('{word} should be authenticated', function (name) {

assertThat(this.isAuthenticated({ name }), is(true))

})

Then('{word} should see an error telling him/her to activate the account', function (name) {

assertThat(

this.authenticationError({ name }),

matchesPattern(/activate your account/)

)

})

This all seems quite straightforward in our simple example, but if we're really sensitive to them, we might notice a couple of issues that could cause concern as the codebase grows.

First, we have duplication of the project name, a-project. We've made the sensible choice to push this detail down out of the scenarios to make them more readable (avoiding incidental details), but we're now left with the problem of needing that information in two places in our code. One solution might be to stash the project name on the World, like this:

When('{word} (tries to )create(s) a project', function (name) {

this.projectName = 'a-project'

this.createProject({ name, project: { name: this.projectName }})

})

Then('{word} should see the project', function (name) {

assertThat(

this.getProjects({ name }),

hasItem({ name: this.projectName })

)

})

If you use Cucumber-Ruby you've probably done this kind of thing using an instance variable. SpecFlow or Cucumber-JVM practitioners maybe have used a ScenarioContext object. Like using helper methods, this is common practice in the Cucumber community. While this will work OK for now, what we're starting to see is that the World object is just getting more and more complicated.

It's becoming a God object.

Well-designed objects have the property of cohesion. That means the methods on that object all have a reason to be together, such as sharing the same internal state. God objects don't have this property. They're just a grab-bag of methods that have no reason to be on the same class other than for a lack of a better place to put them.

Another niggling concern is that we've broken our idiom of having one-liner step definitions. We're introduced the concept of "signing up" which rolls together the two granular actions of creating an account and then activating it.

At this stage, a two-line step definition is not a big deal, but it's the wrong direction of travel. As we build up a more rich and interesting system we'll have more and more of these abstractions. We could push this down into a signUp helper method on the world, but this doesn't actually tackle the complexity, it just pushes it away somewhere we can't see it so easily.

Cracks are appearing

Let's take a step back for a minute and review what we do and don't like about this code so far.

On the up-side:

- The scenarios read really nicely. We're not being forced to put details into the scenarios for the sake of what's easy to code.

- We've got a good separation of concerns, with the step definitions staying simple, delegating the work of actually driving the application to helper methods.

- The language in the step definition code is consistent with the language of the Gherkin steps. For example, we see calls to

signUpandactivateAccountmethods rather than any details aboutclickorfillIn. There's no translation happening in the step defintions, so we can trust them.

But we're concerned that:

- we have duplication of hard-coded details like the name of the project, when we need to share implicit context (i.e. "the project") between steps.

- adding more and more helper methods onto the World means that class will just grow and grow, and it will lack cohesion.

At the moment, in this tiny example codebase, these concerns are only hairline cracks; but we know what happens as our codebase evolves: small problems turn into big problems and, before you know it, you're stuck in a codebase you hate.

What about page objects?

What if we were to use page objects? Could they help us?

Certainly, having different objects to represent the sign up form, the login form, and the new project page, would avoid us lumping all our automation code into one World object. However, this doesn't stop the bloat. Page objects that model every button and interaction point on a page can become huge and unwieldy.

A more insidious problem is that page objects are based around the UI. This means there would have to be a leap in translation in our step defintions: we'd jump from a problem-domain concept like create a project to the nitty-gritty interactions with the app that will cause this action to happen. This isn't such a clean separation of concerns, and distracts us from focussing on the behaviour and intent of our users. If we're not careful, these detailed interactions can start to leak out into the Gherkin.

So now we have a sense of some of the problems with the typical approaches to organising acceptance test automation code.

In the next post we'll have a look at what Screenplay could offer us to solve these problems, and start using it in our example application.