User stories and BDD (part #3) - small or far away?

This is the third in a series of articles digging into user stories, what they're used for, and how they interact with a BDD approach to software development. You could say that this is a story about user stories. And like every good story, there's a beginning, a middle, and an end. This post is a continuation of the middle.

Previously...

In the last post we followed a user story through the process of Discovery. We saw that the main purpose for a user story was to minimise waste by making decisions at the last responsible moment, that accidental discovery is an unavoidable source of waste, but can be minimised by embracing deliberate discovery. We introduced Example Mapping as a deliberate discovery technique and observed that, through discovery, stories are transformed from a placeholder for a conversation into detailed small increments. Now it's time to talk about what we mean by "small" and why, in the context of user stories, small is beautiful.

Small and valuable

The INVEST acronym was created by Bill Wake and popularised by Mike Cohn. It reminds us that stories should exhibit the following characteristics:

- I - independent

- N - negotiable

- V - valuable

- E - estimable

- S - small

- T - testable

This acronym encapsulates good advice about what a user story should look like. I'll write about the other aspects of this acronym in a future post, but for now I'd like to point out the tension that teams usually feel between stories being small and stories being valuable.

Value is often thought of as delivering functionality that will earn money from fee-paying customers. While that is one definition of value, it is very narrow, ignores the incremental nature of value, and encourages teams to work on larger stories than they should.

I have my own definition of value, that is much broader, and fits better with the iterative and incremental nature of agile:

Value is any piece of work that increases knowledge, decreases risk, or generates useful feedback

This definition of value allows us to work on really small stories, but it seems that most teams are resistant even though they typically accept that fast feedback is beneficial.

Why small is beautiful

There's really only one reason to work on smaller stories, which is reduced waste. For that to make sense we need to understand where waste occurs during software development. For the purposes of this article, I’m going to assert that the majority of waste arises from one of two sources: ignorance and disrupted flow.

Ignorance

Software development is a process of learning and we learn by getting feedback. Whether that’s feedback from the customer that we have misunderstood their problem, or feedback from tests that we’ve not understood the limitations, it’s all valuable learning. To learn faster we need to get feedback faster.

The more work we do between each piece of feedback, the more rework we’ll have to do if it turns out that we’ve been building on misunderstandings or incorrect assumptions. If we can minimise rework, then we can minimise the risk that the work we’re doing will be wasted.

And, just to be clear, there are multiple risks that learning (and hence feedback) needs to address. The bigger the story, the higher the risk that it’s hiding some complexities that we’re ignorant of. The earlier that we can reduce that ignorance, the sooner we can begin to decrease our exposure to risk.

Big stories mean we have to wait longer for feedback; smaller stories mean we can get our feedback more quickly.

Disrupted flow

While waste due to ignorance is usually problem-specific, the waste due to the processes that our teams follow are often systematic.

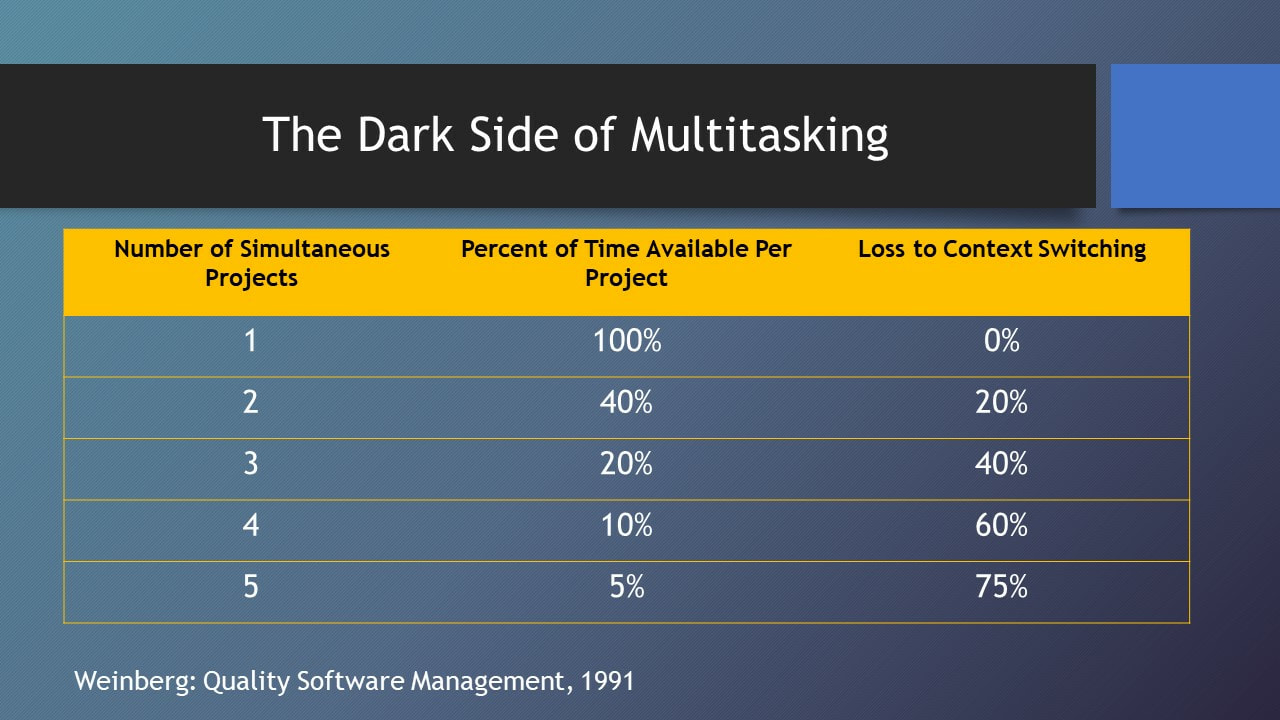

The most efficient way to work on stories is what Lean manufacturing calls single piece flow. Essentially this means that when someone starts work on a story, they can independently take it to completion. The larger the story, the more likely it is that it will contain some obstacle that interrupts its completion. When that happens, the flow of the work will be disrupted and they will generally context switch to another story. Context switching is a major source of waste.

https://madamsonassociates.com/blog/high-cost-of-context-switching

How small is small?

There's a conversation that takes place in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy which neatly describes peoples’ reaction to my answer:

Lunkwill: Do you...

Deep Thought: Have an answer for you? Yes. But you're not going to like it.

As long as a story delivers value (see my definition of value above), then my answer (whether you like it or not) is: the smaller that you can make the story, the better.

The standard objection to this is that it’s just not efficient to do such small pieces of work. But why is it not efficient? Read on….

Transaction cost

The challenge with delivering tiny stories is that our development processes are frequently inefficient. The cost of creating a small story and pulling it through your development pipeline is called the transaction cost. A heavyweight process with, for example, a manual release process involving management sign-off, incurs a high transaction cost for every story. At the other end of the spectrum, a fully-automated Continuous Delivery pipeline has an extremely low transaction cost. The lower you can make this cost compared to the cost of actually delivering a story’s value, the more worthwhile it is for you to ship small stories often.

There are major global corporations that have focused on making their processes efficient -- and they can deliver thousands of tiny stories into production every day. Most organisations still think that demonstrating a new piece of functionality every two weeks is quite advanced.

To maximise the efficiency of our development teams we should focus on improving their flow. It took Toyota years to get to where they are today, but they didn’t stop making cars while they improved their production processes -- and we shouldn’t stop delivering software.

Before your next retrospective read The Bottleneck Rules (a very short book) and think about applying some of the techniques that it describes.

Low fidelity stories

Small stories will often be low fidelity stories. Fidelity refers to the finesse of the feature, or solution -- low fidelity solution will be low in things like precision, granularity, or usability, but will still [help us learn how to] solve the original problem. The goal is to do as little work as possible to learn whether we’re progressing in the right direction.

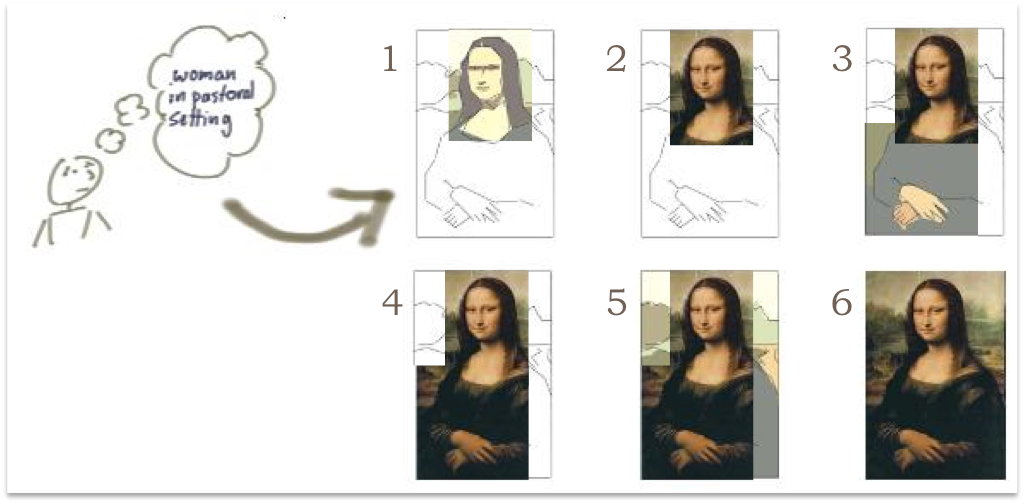

Jeff Patton uses the analogy of painting the Mona Lisa to demonstrate the difference between iterative and incremental development. The first story would deliver an outline of a part of the composition, with future stories

- iterating on the outline by adding colour, texture, and detail

- incrementally extending the outline to cover more of the composition

http://itsadeliverything.com/revisiting-the-iterative-incremental-mona-lisa

Agile teams work both iteratively and incrementally, starting with low fidelity stories that allow us to learn fast and early.

Individual stories don’t necessarily have to be something coherent enough to release to your users. You may need to complete several detailed small increments before you’ve added enough value that your users would appreciate or even notice it. The way you choose to slice your stories becomes a really important skill, so that you’re able to gradually fade up the fidelity until you’re ready to ship.

Story slicing

Once you accept the benefits of small stories, there’s still the challenge of creating them. There are many techniques for decomposing stories into thin slices, but I’d like to share three nuggets that you should keep in mind.

Asteroids

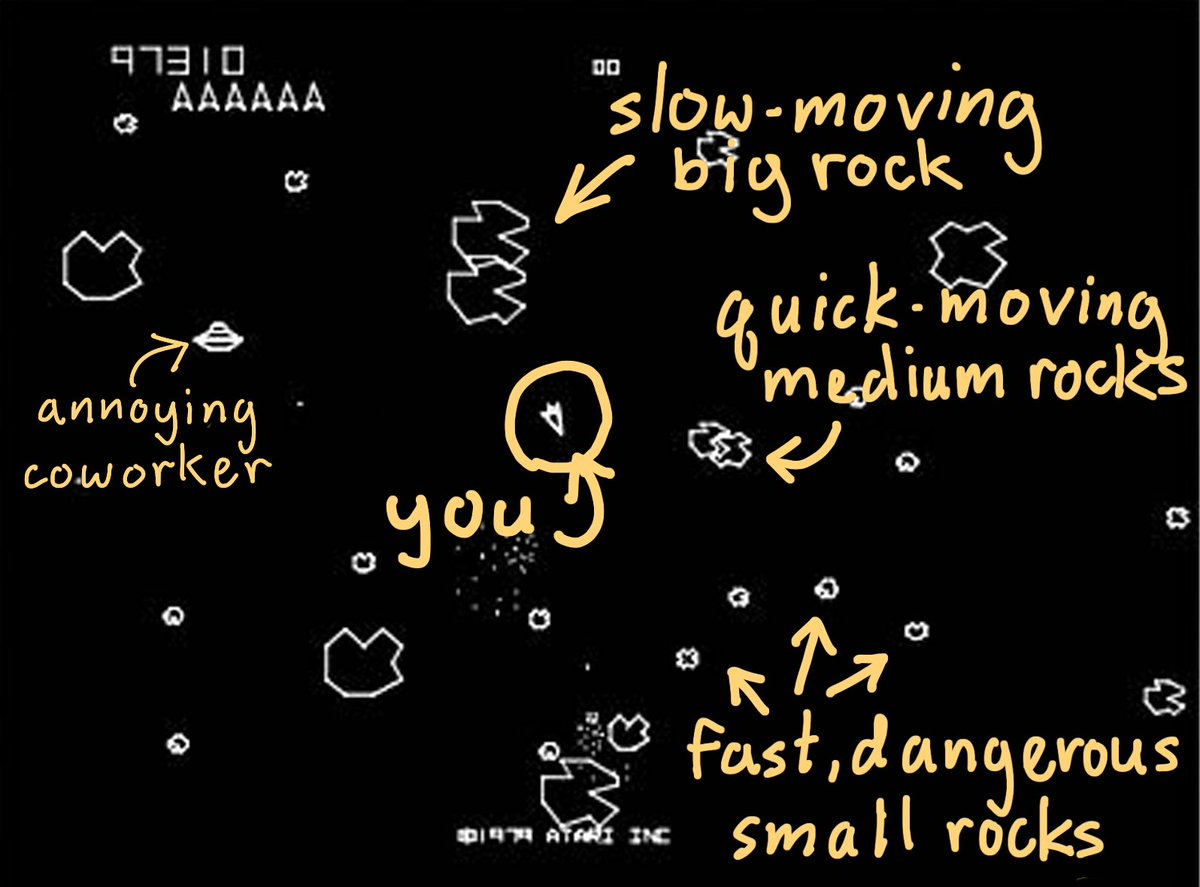

In his book User Story Mapping, Jeff Patten draws an analogy with the old arcade game Asteroids. The decomposition of large, slow-moving rocks into tiny, fast-moving, dangerous rocks is instructive.

The worst technique in Asteroids is to break all the big rocks into medium rocks, and all the medium rocks into tiny rocks. The outcome, if you do this, is a screenful of fast moving, dangerous rocks that inevitably destroy your spaceship.

A similar thing happens if you try to populate your entire backlog with tiny stories. You have a backlog that’s impossible to manage, full of duplicate and out-of-date stories. Instead, break off a chunk at a time and decompose that into small stories, leaving the backlog mostly full of big and medium stories.

Example Mapping

Example Mapping is a technique that can really help slice a medium story into a set of small stories. It’s well described elsewhere and provides a structured way to collaboratively analyse a problem and generate concrete examples of how the system should actually behave.

The beauty of this technique is that the example map itself visually communicates whether the story is too big AND gives us a simple mechanism to slice it up. Because the product owner is present during example mapping, this approach has the added benefit that business priorities can be taken into account at a very fine granularity.

The flowchart

Example mapping is my go-to technique when analysing and slicing a story, but it’s by no means the only way to do it. Richard Lawrence created the extremely useful How To Split A User Story flowchart. Print this out (on a LARGE piece of paper) and hang it on your team’s wall.

Two week iterations

To learn fast and maintain flow you need stories to be significantly smaller than your iteration. For most XP and Scrum teams, this means that every story should be deliverable (from Backlog->Done) in 3 days or fewer. This is hard, but the benefits are immense.

Small or far away?

Once you set about trying to work with smaller stories, you’ll probably find that, even after slicing them, they’re still bigger than you would like. The challenge is that until you really dig into the details of a story, some of its complexity remains stubbornly hidden.

]

]

https://www.agilealliance.org/resources/videos/how-long-is-a-piece-of-string/

As Father Ted, discovered -- it’s all a matter of perspective.

Next time

In this post, I've indulgently allowed myself to rant about why stories should be small. Really small. Next time, I'm going to try to pull this all together to convince you that there’s no place for stories inside your feature files.