Can all testing be automated?

I’m continuing to answer questions that were asked during my session “Are BDD and test automation the same thing?” at the Automation Guild conference in February 2021. This is the fourth of five posts.

- Why should automation be done by the dev team?

- Isn’t the business-readable documentation just extra overhead?

- What’s wrong with changing the scenarios to enable automation?

- Can all testing be automated?

- How can Cucumber help us understand the root causes of failure?

The question

Isn't the goal of repeatability for refactoring confidence, not test confidence?

In the presentation I gave at the Test Automation Guild conference, I compared traditional test automation to Behaviour-Driven Development. I used a scene from one of my favourite movies, Kelly’s Heroes, to describe the inherent risk that comes from excessive reliance on our automated tests. More on that later.

This question hints at the tension between automated tests and confidence in our software. How many tests is enough? What sort of tests give us the most useful information? Where is the sweet spot that maximises the return on automated test investment?

Repeatability

I’ve written at length about the test automation pyramid, so I’ll not repeat most of that here. There is an important conclusion that I do want to summarise, and it’s this:

We invest in small, fast, repeatable tests (at the bottom of the pyramid) because they only fail when there’s a problem with the thing that they were created to test

They shouldn’t fail because some other part of the software has a problem. They shouldn’t fail because some external service is having a temporary outage.

This means that we will avoid the flickering test - the scourge of automated tests. When one of these tests fails, we can be confident that there really is a problem in that specific part of the software. And finally, the amount of debugging detective work that we’ll need to do is minimised.

Minefields

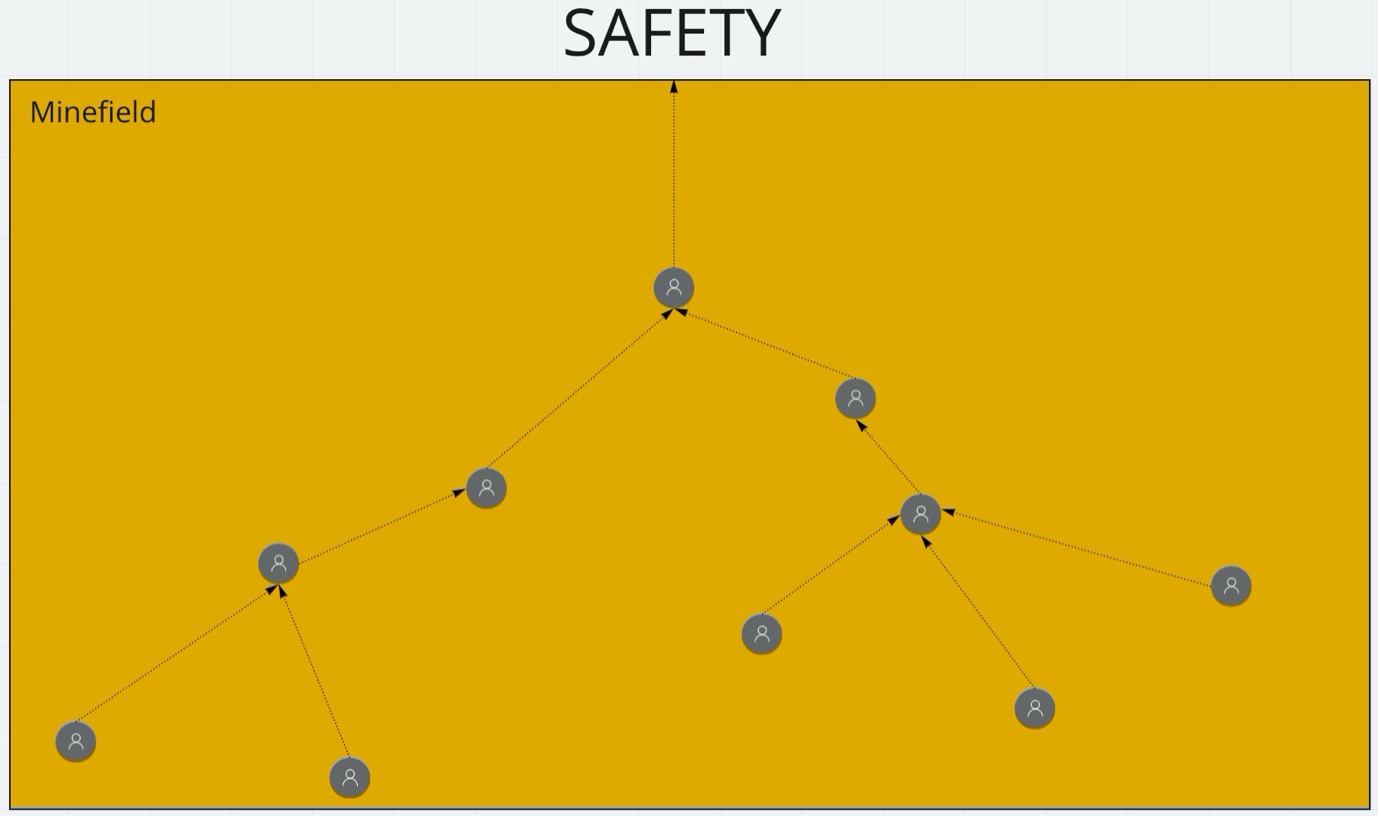

In Kelly’s Heroes the platoon wander into a minefield. Everything seems fine until one unlucky soldier steps on a mine. To get out safely, the person that is nearest the edge of the field carefully works their way forward, probing for mines as they go. Everyone else works towards their nearest colleague. The end result is the minimal number of paths that are guaranteed to be safe.

If another platoon needs to cross that field, they could follow the paths marked out by Kelly’s platoon and be guaranteed to get across safely. That doesn’t mean that there are no mines in the field – just that, by following the safe paths, they’re guaranteed not to step on any.

Automated tests are like paths through the minefield. If a test does fail, then you fix the defect, and the test will now pass – every time it runs. Any defects not already detected, will never be detected by the automated tests. That’s not to suggest there is no value in the automated tests. As suggested by the original question, the continuing value of a passing automated test is to prevent a regression from creeping in (either during refactoring or during development of a new feature).

My friend Gojko Adzic has spoken about the decreasing value of an automated test over time. He interviewed a team at uSwitch that only ran a subset of their tests regularly. I've even come across people that suggest deleting tests if they haven’t failed for a certain period of time. Personally, I encourage teams to think of automated tests as documentation of expected system behaviour. Only delete a test if it doesn’t contribute to an overall understanding of how the system is intended to behave.

Explore!

To be confident that your system will behave correctly in all possible situations, perhaps you might consider exhaustively testing every possible path through the software, using every possible data value. It doesn’t take long to see that this is impractical. Instead, testers frequently reduce the test space by using partitioning techniques that can dramatically reduce the number of tests needed, without massively reducing your confidence in the outcomes.

Even so, given the inherent complexity of modern software systems, there are many modes of failure that are hard (or impossible) to predict. Therefore, test plans and automated tests will naturally not catch many categories of defects. One widely accepted approach to rooting out these sorts of problems is called Exploratory Testing – as described in the excellent book Explore It! by Elisabeth Hendrickson.

From my perspective, the key aspects of Exploratory Testing that should be kept in mind are:

- It’s a job for an experienced tester

- Testers with relevant domain knowledge are ideal

- It’s not a checkbox activity

- Ongoing exploration as the product evolves is essential

- It complements automated testing

- Refer to the Agile Testing Quadrant from Janet Gregory and Lisa Crispin’s Agile Testing book

Alternatives

As well as exploratory testing, there are many other approaches to reducing the likelihood of defects in your software. A few of them (in no particular order) are:

- Mutation testing – tooling that injects defects into the codebase, one decision point at a time (to create a mutant). The automated tests are run against each mutant – if no tests fail then there’s something missing from the test suite.

- Chaos engineering – interfering with running systems to ensure that they are resilient in the face of degradation and failure.

- Blue/Green deployments – deploying the latest version of the system in parallel with the current version. A proportion of users are then directed to the latest version and are monitored to ensure that users are still able to achieve expected outcomes.

- Stack-trace driven development – ship the software without testing it and let your users report defects to you.

Conclusion

Repeatability of automated test is needed for confidence in the quality of the software and the quality of the tests. The first thing that happens when an automated test begins to fail intermittently is that confidence in the test suite as a whole begins to suffer (see the Broken Windows theory).

The challenge with a finite suite of automated tests is that they continually check exactly the same paths through the software. By definition, therefore, they can’t detect defects that lie off those paths. There are a host of approaches that you might adopt, based upon your organisation’s attitude to risk, but the most effective is often to supplement automated testing with exploratory testing.