Who writes the scenarios?

This was originally posted on Matt's personal blog.

Barbara is a business analyst.

Until recently, Barbara hated BDD.

When her company first adopted Agile, lots of things changed. She was told she no longer needed to write requirements documents. Instead, she was expected to express the business user’s requirements as something called User Stories and put them into their Agile project management tool.

Jordan, their old Agile Coach, had told Barbara that each User Story needed to have acceptance criteria. When Barbara asked Jordan what acceptance criteria were, he was pretty vague. “Just write whatever you need so that the developers will understand what you want them to build”. He said.

So she did.

One thing Barbara liked about the move to Agile was that she sat with the team, instead of with all the other business analysts like she used to. She did miss her BA buddies but they still met up for lunch every Thursday and went for pizza at the mall across the road. Sitting with the team meant she got into lots more conversations with them about the work they were doing together, and had a chance to share some of her deep knowledge of the business domain.

So it didn’t matter too much what she wrote in the acceptance criteria. After all, as Jordan said, a user story is just a token for a conversation.

Then one day, the team got a new Agile coach, Nigel.

Nigel told Barbara that she should write all of her acceptance criteria using a new format: Given, When, Then. He said she didn’t need to spend so much time talking with the developers. Nigel said that was inefficient.

Nigel said that she should try to record everything she knew about each requirement using this Given, When, Then format. It felt kind of awkward, but she gave it a go.

Nigel said that the advantage of using Given, When, Then was that not only were they requirements for the developers, but the testers could use them for automated testing too. Nigel said this was called BDD. Barbara was starting to find Nigel quite irritating.

Anyway, Barbara carried on like this for a while. Her job became more lonely. She wrote up her user stories, and her Given, When, Thens, and assigned the stories to the developers in their Agile project management tool. The atmosphere in the team changed. People didn’t talk so much any more. It started to feel like the old days, except that she had to use this stupid fiddly project management tool and this silly Given, When, Then format — or “Gherkin” as Nigel insisted on calling it for some reason — for all her requirements, instead of just opening up Microsoft Word.

Barbara complained to her buddies on Thursdays about BDD. One of her friends, Carol, who was working in a different division of the company now where Jordan was coaching, seemed surprised.

“Wait, who do you say writes the scenarios?” asked Carol.

“I do”, said Barbara, “who else do you think could do it? The developers don’t seem to know enough about what the product does. And anyway, Nigel says they’re too busy to talk to me.”

“Too busy my ass! Busy writing code that does the wrong damn thing I’ll bet!” said Carol. “Let me tell you how we do it on my team.”

Barbara blushed a little at Carol’s language, but she couldn’t hide her smile. She really admired Carol’s up-front style. She listened as Carol explained.

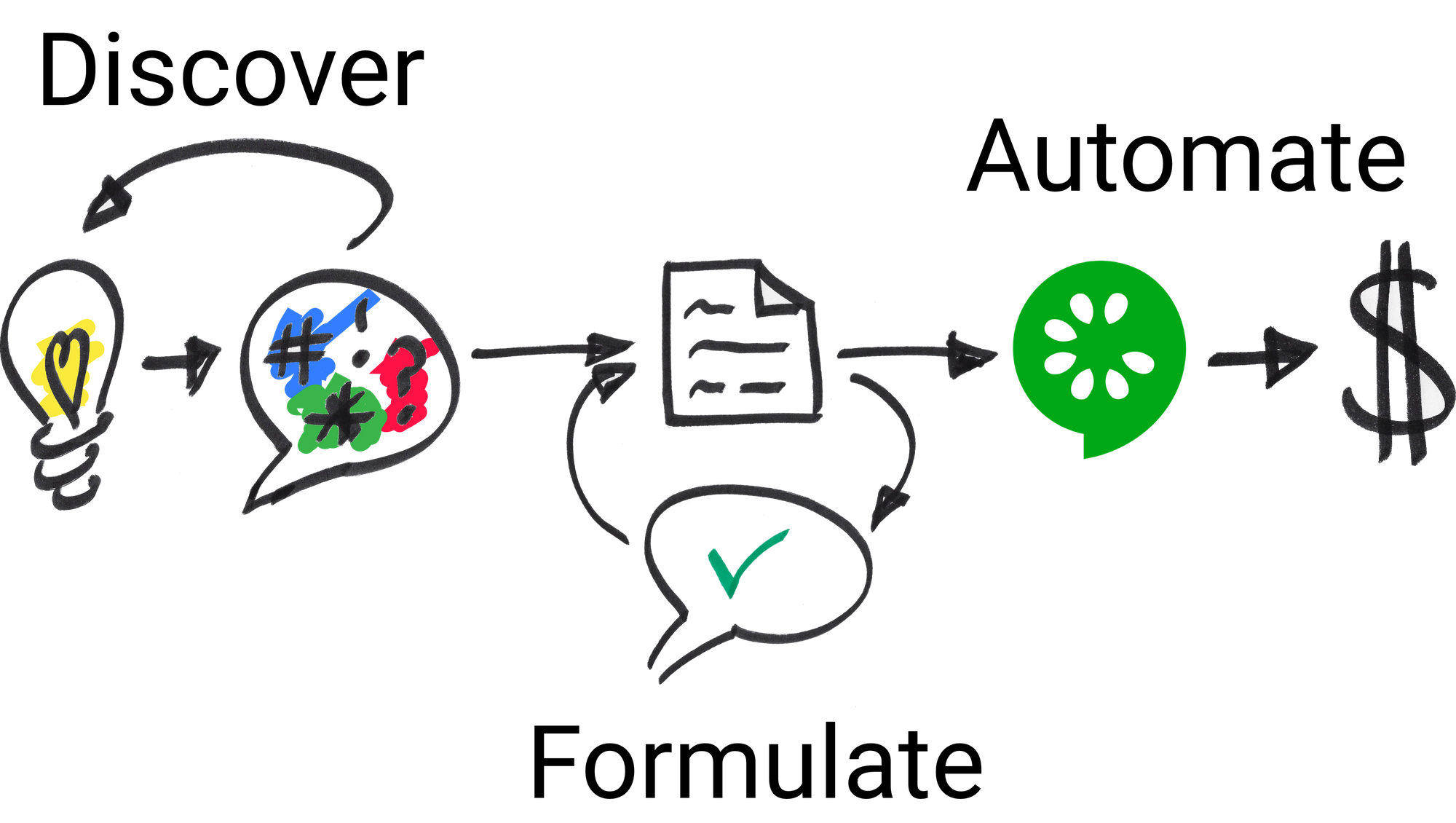

“BDD is all about learning early. About deliberate discovery. About embracing your ignorance. If you have the person with the most domain knowledge write the scenarios, you’re missing a learning opportunity. That is a weak-ass move.

“Instead, use the act of writing the scenarios as feedback.

“Start with a conversation including at least the BA, tester and developer, to talk through the scope of the story. You can use example mapping or some other way to manage that conversation, but keep it quick and focussed.

How BDD teams work

“Next, have the people who learned the most in that conversation — that’s generally going to be the tester and developer — go off and write down what they heard as scenarios.

“Now they share those scenarios back with you, the domain expert, and see if they got it right. They test their understanding. Writing scenarios is so much cheaper than writing code, and we all know it’s much cheaper to fix a mistake before it gets into the code.

“You might need to go around this loop a few times to get it right, but that’s good. Better than waiting until they already coded up a bunch of shit you never wanted, right?

“Anyway, once everyone’s happy that those scenarios describe the thing as we want to build it, the team can automate it and use Cucumber to guide them as they write the code.”

“This sounds really good,” nodded Barbara, her eyes gazing idly out of the window. “Now how am I going to convince Nigel to let us try it…?”