Introducing Example Mapping

Before you pull a user story into development, it’s crucial to have a conversation to clarify and confirm the acceptance criteria.

Some people do this during their backlog refinement or planning poker sessions. Other teams have a specific three amigos meeting, specification workshop or discovery workshop.

Whatever you call this conversation, many teams find it hard; it’s unstructured, it takes too long and gets boring. The result is they don’t do it regularly or consistently, or maybe they just give up on it entirely.

I’ve discovered a simple, low-tech method for making this conversation short and powerfully productive. I call it Example Mapping.

How it works

Concrete examples are a tremendous way to help us explore the problem domain, and they make a great basis for our acceptance tests. But as we discuss these examples, there are other things coming out in the conversation that deserve to be captured too:

- rules that summarise a bunch of examples, or express other agreed constraints about the scope of the story.

- questions about scenarios where nobody in the conversations knows what the right outcome is. Or assumptions we're making in order to progress.

- new user stories we discovered or sliced and deferred out of scope.

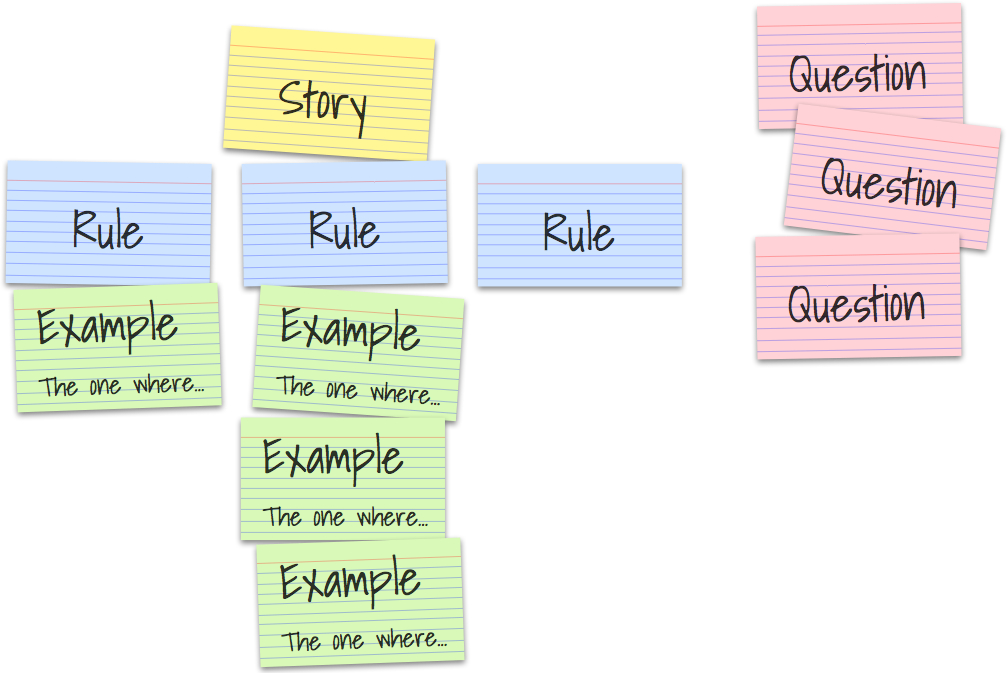

Example Mapping uses a pack of 4-coloured index cards and some pens to capture these different types of information as the conversation unfolds. As we talk, we capture them on index cards, and arrange them in a map:

We start by writing the story under discussion on a yellow card and placing it at the top of the table.

Next we write each of the acceptance criteria, or rules that we already know, on a blue card and placing those across the table beneath the yellow story card.

For each rule, we may need one or more examples to illustrate it. We write those on a green card and place them under the relevant rule.

As we discuss these examples, we may uncover questions that nobody in the room can answer. We capture those on a red card and move on with the conversation.

We keep going until the group is satisfied that the scope of the story is clear, or we run out of time.

And that’s it. I told you it was simple!

Instant feedback

As the conversation flows, we quickly build up a visual representation on the table in front of us reflecting back our current understanding of the story:

- A table covered in red (question) cards tells us that we still have a lot to learn about this story.

- A table covered in blue (rule) cards tells us that this story is big and complicated. Perhaps we can slice it? Take another yellow (story) card and put the sliced story on the backlog.

- A rule with many examples might be over-complex. Are there multiple rules at play that need to be teased apart?

You’ll find that some rules are so obvious you don’t need examples at all. It’s clear from the conversation that everyone understands the rule. Great! You can all move on with your lives without forcing yourselves to grind out examples like BDD-brainwashed automatons.

Thinking inside the time-box

A small group of amigos should be able to map out a well-understood, well-sized story in about 25 minutes.

If you can’t, either you’re still getting the hang of this (which is fine), the story is too big (definitely not fine), or it still has too much uncertainty in it. Listen to that, and either try and slice the story, or let the product person go off and do some homework before you put story back into another example mapping session at a later date.

At Cucumber, we use a quick thumb-vote after 25 minutes to determine whether we think the story is ready to pull into development. Even if there are some questions remaining, you might think they’re minor enough that you can resolve them as you go. Let the group decide.

Benefits

Example Mapping helps you zoom in and focus on the smallest pieces of behaviour inside your story. By mapping it out you can tease apart the rules, find the core of the behaviour you want, and defer the rest until later. With this level of scrutiny, example mapping acts like a filter, preventing big fat stories from getting into your sprint and exploding with last-minute surprises three days before demo-day.

It also saves time, and so helps maintain busy product people’s interest in the process.

Many teams assume that the three amigos should write acceptance tests (e.g. Cucumber scenarios) during this session, sitting around a projector while someone types formal gherkin scenarios into an IDE. There are occasions when this is valuable, but generally I think it’s a bad idea. It can actually be distracting from the true purpose of the conversation.

It’s easy to see why people make this mistake: the apparent purpose is to take a user story, which already has some pre-defined acceptance criteria, and come up with examples that can be turned into acceptance tests.

I think the true purpose, however, is to reach a shared understanding of what it will take for the story to be done. You can move much more quickly towards this goal by staying low-tech.

Friends episodes

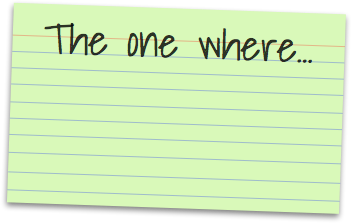

So instead of going for full-blown formal Gherkin scenarios, just try to capture a list of rough examples, using the friends episode naming convention.

For example:

- The one where the customer forgot his receipt

- The one where the product is damaged

- The one where the product was bought 15 days ago

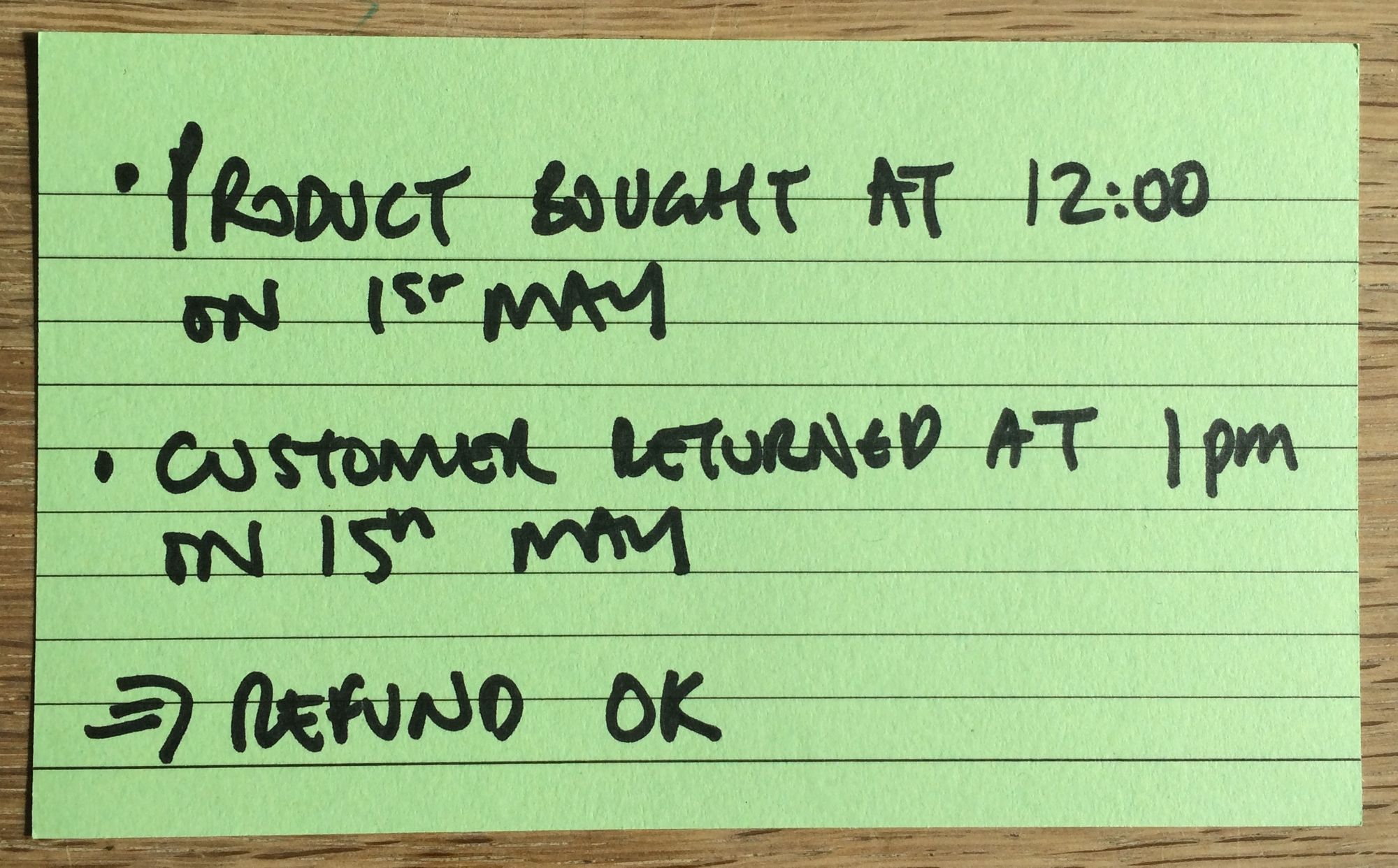

Sometimes, when uncertainty lurks, you’ll instinctively want to be more concrete than this. You still don’t need to resort to the rigid structure of Given When Then just yet:

When the outcome (Then) is unclear, you don’t have an example, you have a question.

Known unknowns

Whenever a conversation like this is going round in circles, it’s because you don’t have enough information. Probably someone is missing from the conversation, or maybe you need to do some user research, or a spike.

Instead of letting everyone share their opinion about what they think the outcome should be, simply capture the question and move on. Congratulations! You’ve just turned an unknown unknown into a known unknown. That’s great progress.

Many people tell me that just this one aspect of example mapping has transformed their discovery workshops from dull ramble-athons into snappy productive mind-melds.

Who should come?

The bare minimum is your three amigos: a developer, a tester and a product person. That’s just a minimum though. By all means invite your operations, user experience people or whoever else is relevant to the story being discussed. Anyone likely to help you discover new questions, or to turn questions into decisions during the conversation will be useful.

While you’re learning this technique, it can help to have someone in the formal role of facilitator, whose job it is to make sure everything that’s being said is being captured on a card. Examples and questions fly around the room quickly, and it takes discipline to capture them on the table so you can see what you’re talking about.

So when do we write Gherkin?

Don’t let this post confuse you: there is immense value in writing Gherkin together too, especially during the early days of a project. That’s where you develop your ubiquitous language, and it’s vital to have those scenarios expressed in a way that everyone on the team believes in.

But expressing examples in that way requires a different mode of thinking from deciding which examples are in scope, and clarifying the underlying rules.

For a team that’s up and running, with a fairly mature domain language, my preference is for the product person to spend their time and energy in the example mapping session, and leave the actual writing of Gherkin to their other two amigos. Once they’ve drafted a Gherkin specification, the product person can give them feedback.

Is that how I would have written it?

This gives you an opportunity to test how effective the example mapping conversation was in transferring the product person’s knowledge to their amigos.

How often should we do this?

Product people are often busy. Respect their time by scheduling these sessions in a way that they’ll be able to give you their full attention.

My recommendation, based on what I’ve seen work for several teams in practice, is to run them frequently: every other day is often a good rhythm. Just pick one story and give it 25 minutes of attention, then go back to work. Trying to do more in a big batch will just drain your energy.

But my team is distributed!

I’ve seen innovative hacks on this already: some people use bullet lists in a shared Google doc, I’ve seen people using a spreadsheet with coloured cells to represent the cards. You could also use a mind-map. The key is to keep it quick and easy to work with, so you can focus on the conversation.

Some final tips

It’s important to clearly understand the distinction between rules and examples before you can make use of Example Mapping. I have a fun exercise for teaching this that I’ll share in a future post.

Remember that the whole purpose of this conversation is to discover the stuff you don’t already know. So there are no stupid questions. Have some fun and really explore the problem.

You’ll find that rules make natural fault lines for slicing your story. Try to feel comfortable deferring as much as possible, so that you can focus on solving the core of the problem. You can add more sophistication (and complexity) later.

Thanks to Janet Gregory, Aslak Hellesøy and Seb Rose for their feedback on this post, to Theo England for his patience while I perfected it, and to Tom Stuart for getting me to pull my finger out.

This article has been translated into French (Thanks, Nicolas Mereaux!) and Japanese (Thanks, Yuya Kazama!)