I’m continuing to answer questions that were asked during my session “Are BDD and test automation the same thing?” at the Automation Guild conference in February 2021. This is the last of five posts.

- Why should automation be done by the dev team?

- Isn’t the business-readable documentation just extra overhead?

- What’s wrong with changing the scenarios to enable automation?

- Can all testing be automated?

- How can Cucumber help us understand the root causes of failure?

The question

“Specific about Cucumber reporting. I find that sometimes a single bug can break several Given-When-Then scenarios, which is great to measure business impact, but not great to understand root-causes/bugs. Any ideas on this? We ended up creating a complementary root-cause report...?”

This is a very interesting question that requires us to think about the purpose of our tests. You’ll probably be familiar with the popular test characterisations of unit, integration, and end-to-end – as well as many more.

Do we need unit tests AND end-to-end tests? If so, what different concerns do they address? If not, then which should we prefer? In answering this question, I’ll refer to two metaphors (one well known, the other less so) and an acronym.

Test automation pyramid

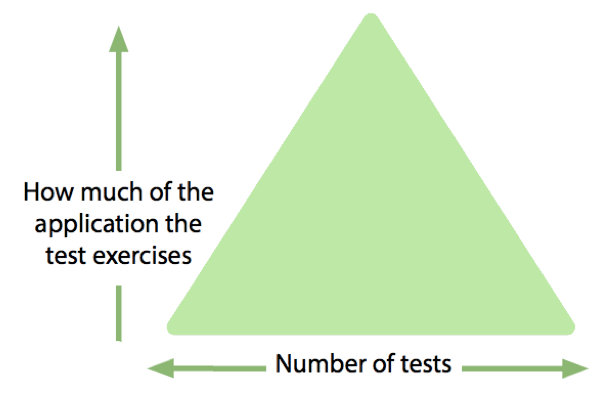

The test automation pyramid has been widely discussed in the industry for many years.

I wrote a lengthy blog post on the subject a few months ago, which I will not repeat here in its entirety, but there is a section that directly addresses the question:

[Tests at the bottom of the pyramid] should exercise as little of the application as they can. These tests should document the behaviour and validate the correctness of small amounts of code.

As we move up the [pyramid], we will write fewer tests, but they will exercise progressively more of the application. At the same time, the intent of the tests changes to documenting the interaction between components, the messages they pass between each other, and the protocols that they use. This includes behaviours such as validation and error handling.

When we reach the top of the [pyramid] we are exercising the whole application. We should already have confidence that each component behaves as intended. We should also have confidence that each interaction between components has been exercised to verify that both ends of the dependency have the same understanding of the protocol that they share. All that remains is to verify that “the system hangs together.” These are sometimes characterised as smoke tests, and they check that the application has been deployed successfully and correctly configured for that specific environment.

The foundation of your automated testing strategy is the small, fast, reliable tests at the bottom of the pyramid. If there is a defect in the code, then it should be caught by one of these tests. Since each test at the bottom of the pyramid is validating the “correctness of a small amount of code”, we expect only a single test to fail for any given defect.

Many high-level tests might depend on the code that contains the defect, but we would expect the build to fail and terminate before running these high-level tests. The foundation has been found to be defective – so there is no point running tests that depend on the foundation being sound.

Test automation iceberg

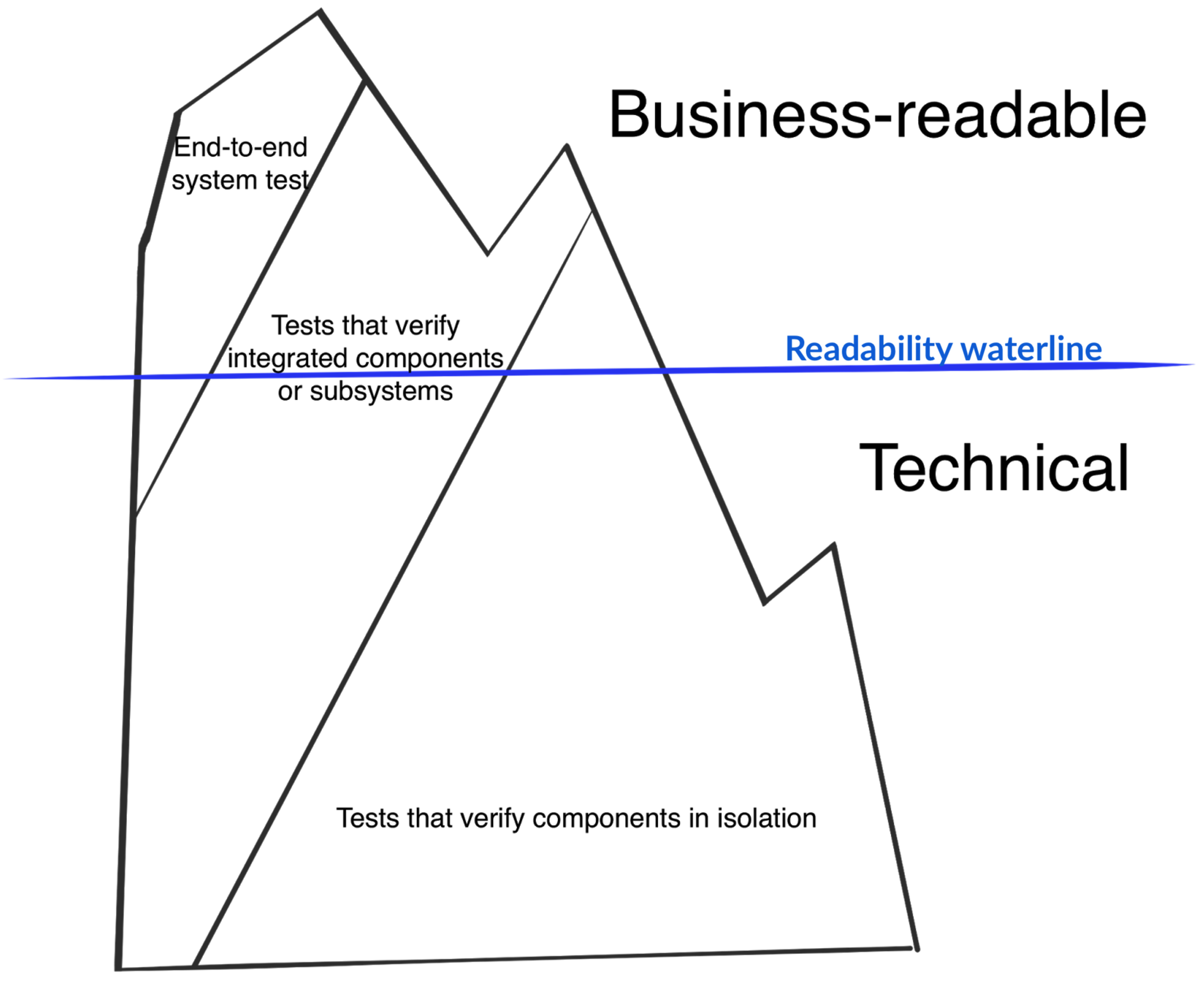

If the low-level, programmer tests fail, then it is almost never worth invoking Cucumber, but this doesn’t necessarily fix the problem encountered by our questioner. In another blog post, I document an insight that my colleague Matt Wynne shared with me some years ago, which he called the test automation iceberg. The one-line summary of that post is that:

Not all Business-readable tests need to be End-to-end and not all End-to-end tests need to be business readable

So, Cucumber scenarios may be implemented to run anywhere in the test automation pyramid. The use of business-readable scenarios tells us only that the behaviour is of interest to the business – it says nothing about how the test itself is automated.

BRIEF

In the second volume of the BDD Books series, Formulation, Gáspár Nagy and I introduce the BRIEF acronym. The last letter in the acronym, “F”, stands for “focused” which we describe in this way:

Focused: Most scenarios should be focused on illustrating a single rule.

What this means is that we should attempt to implement our scenario automation as far down the pyramid as possible, to ensure that we are validating a single behaviour. If there’s a defect in the implementation of that behaviour then only one (or a few related) scenarios should fail. This gets to the heart of the original question.

In Formulation, we differentiate between illustrative scenarios (that are focused on a single rule) and journey scenarios (that document a flow through several/many behaviours of the system). If illustrative and journey scenarios are run at the same time, then a defect in the implementation of a single behaviour may cause the failure of many journey scenarios. Cucumber provides several mechanisms for separating your scenarios into discrete suites that can be executed independently (see the free training video BDD with Cucumber, chapter 6 for some suggestions). Aslak Hellesøy has also described how a hexagonal architecture can be leveraged to implement illustrative scenarios at several locations within the pyramid.

Conclusion

The foundation of an automated testing strategy should be built from the small, fast, reliable programmer tests that are popularly called unit tests. When there’s a defect in the code, you should expect one (or perhaps a few) of these tests to fail – not many. If any of these tests fail, then the foundation is unsound, and it is not worth running the higher level tests that are built on top of this broken foundation.

If a single defect is causing many unrelated tests to fail, then it is likely that you are either:

- running tests higher up the pyramid, even though lower-level tests have already failed, or

- you are missing the necessary lower-level tests that validate the behaviour in which the defect is located.

In summary, Cucumber is a tool designed to support BDD. It will parse business-readable specifications and, in response to each statement, execute relevant automation code that your team has written. To minimise the need for costly root-cause analysis when a defect is introduced, follow the test automation pyramid metaphor and the BRIEF acronym.

Post-script

I salute the original questioner for their implementation of a root-cause report but suggest that it might have been better to have instead written sufficient lower-level checks to catch these defects. Whether the checks should be implemented directly in the programming language of the application (programmer tests) or using business domain terminology (Cucumber scenarios) should depend on whether the business is sufficiently interested in the behaviour that the check documents.

Further, I compliment the original questioner for the correct usage of the often-misspelled word

complementary.