Better requirements by harnessing the power of examples

Writing good requirements is a challenge, especially if they’re intended to be understood by someone other than their author. The more complicated a project gets, the harder it is to communicate the requirements in an unambiguous way. It’s easier to ask someone to cut the grass than it is to describe a design for a flower bed.

By the time we get to designing software systems, the complexity is such that requirements are a collaborative effort that need to be recorded in a structured way. During the 20th century, various formal and semi-formal approaches were integrated into a waterfall model – where each project had distinct, gated phases and each phase had defined outputs, such as “requirements specification”. These approaches to requirements management did not remove the risk of project failure, while adding considerable upfront costs that were often unjustified in the rapidly changing business environment.

The Road to Nowhere, Glasgow

The evolution of agile ways of delivering software removed the phased approach to defining detailed requirements in favour of incremental, just-in-time requirements definition. A side effect was a perceptible decline in enthusiasm for documentation of any kind. Instead, user stories were misused as agile requirements, causing ambiguities that inevitably led to rework and stakeholder dissatisfaction.

What can we do to avoid ambiguous requirements without imposing excessive financial or time costs on our projects?

Crosswalks

It is dangerous for pedestrians to cross roads, so someone came up with the idea of crosswalks and signals. The goal might have been: “let’s install signals that tell pedestrians when it’s safe to cross the road.”

One of the user stories for a safety signal at a crosswalk might have looked like this:

As a pedestrian

I want clear signalling at a crosswalk

So that I can be safe when crossing the road

Attached to the card is the following acceptance criteria (AC):

- There should be separate signals for “safe to cross”, “not safe to cross”, and “safe to finish crossing, but not safe to start”

Take a minute to think about the goal, the user story, and the acceptance criteria. Is there any scope for misunderstanding? If so, how would you confirm your understanding of what’s being asked for and surface any ambiguity?

Illustrating using concrete examples

Concrete examples are used in all walks of life to clarify rules. We use them when teaching our children:

“When you come to a cross-walk, if the signal is red, then you shouldn’t cross the road.”

“When can I cross the road?”

“You can cross the road if the signal is green.”

“What if the red signal is flashing?”

“The flashing red signal means that you shouldn’t start to cross the road. If you’re already crossing the road, then keep going, because the signal will turn to solid red soon.”

This conversation includes a number of examples that were used to clarify how to behave at a crosswalk:

- Arrive at a crosswalk

Signal is green

Cross the road - Arrive at a crosswalk

Signal is solid red

Don’t cross the road - Arrive at a crosswalk

Signal is flashing red

Don’t cross the road - Crossing the road on a crosswalk

Signal starts flashing red

Finish crossing the road

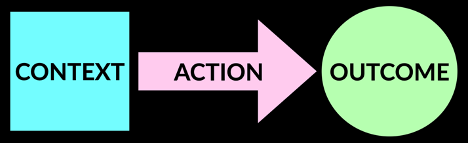

These four concrete examples exhibit the structure that’s common to all concrete examples – they consist of three parts: context, action, and outcome:

- Context: the initial state of the system. In this case, where you are in relation to the crosswalk

- Action: an input or event that causes a behaviour. In this case the state of the crosswalk signal

- Outcome: the resulting intended behaviour. In this case whether to start/continue crossing or not

Clarifying using concrete examples

Concrete examples aren’t just useful for illustrating the intended behaviour of a system. They’re also useful for challenging and clarifying the underlying intent. Consider these examples:

- Colour-blind pedestrian arrives at a crosswalk

Signal is green

??? - Blind pedestrian arrives at a crosswalk

Signal is green

??? - Crossing the road on a crosswalk

Signal turns solid red

???

The question marks in these examples indicate that the user story is insufficient to achieve the goal. In fact, crosswalk signals typically use more than just colours to indicate whether to walk or wait and many crosswalks have audible signals as well.

And what should you do if the signal goes solid red while you’re on the crosswalk? Stop walking? Walk faster? Panic?

The concreteness of an example helps us consider how a system should behave in specific situations. This engages our brain at a level of detail that doesn’t happen when we consider things in the abstract, which is why concrete examples are so powerful when it comes to clarifying requirements.

So many examples

As you can see, it’s easy to generate lots of concrete examples, but more is not necessarily better. Having too many examples can make it hard to see what’s important, as well as imposing a maintenance burden when the business needs change. There are two common ways of managing the volume of examples.

The first is to ensure that all examples are valuable. If two examples illustrate the same behaviour, then remove one of them. One way of demonstrating the value is by giving each example a name that explains why it exists. From the crosswalk examples, some names could be “Signal is green”, “Signal is solid red” and so on.

The second is to separate the examples according to the aspect of the requirement that the example illustrates. Even though all seven examples listed above illustrate the user story’s motivation of telling pedestrians when it’s safe to walk, that user story can be thought of as having several separate acceptance criteria:

- Sighted person at crosswalk should be informed if it is safe to cross

- Sighted person on crosswalk should be informed that it will soon become unsafe to be on the crosswalk

- Colour blind person at crosswalk should be informed if it is safe to cross

- Blind person at crosswalk should be informed if it is safe to cross

Acceptance criteria are a common component of user stories, but they are frequently misunderstood as test cases. Instead, you should think of acceptance criteria as rules that need to be satisfied for a user story to be considered delivered.

Spot the requirement

Requirement itself is an ambiguous term. The goal of telling pedestrians when it’s safe to cross the road is a requirement. The user story describes a safety requirement from the perspective of a pedestrian. The acceptance criteria also describe requirements, but at a finer granularity.

They are all requirements, but as we have seen, it is harder to reason about large, abstract concepts than about detailed, concrete concepts. For the remainder of this post, when I use the word “requirement”, I will be using it in a general, hand-wavy way to mean “some need that the system must satisfy”. Most of the time I will be more specific and use the following terms:

- User story: a narrative description of a need that serves as a “placeholder for a conversation”

- Rule (a.k.a. acceptance criteria): a fine-grained description of a required behaviour of the system

- Concrete example: a single combination of context-action-outcome that clarifies how a rule should behave

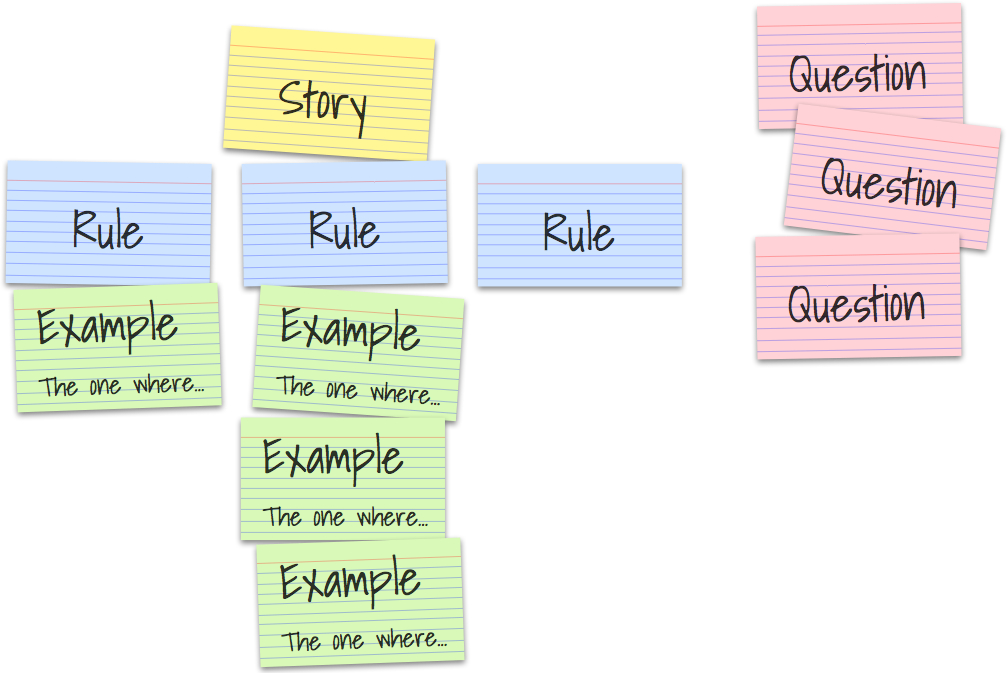

Example Mapping

The Cucumber team have been using a technique called Example Mapping for almost ten years to power structured, collaborative conversations in agile teams. It was discovered by Matt Wynne and through his blog post on the subject, and many consulting engagements, it has gone on to improve requirements for countless teams across the world.

I don’t propose to repeat the whole of Matt’s excellent blog post here. Instead, I’d like to summarise some of the major advantages that example mapping brings:

- Short, frequent example mapping workshops: short timespans allow people to focus; high frequency maintains momentum

- Full engagement of all participants: there are cards and pens for all

- Visual feedback: the example map will tell you if the story is ready to be worked on

- Actionable outcomes: question cards are allocated to participants; answers will feed into the next session

Originally, example mapping required teams to be collocated, with access to 4 coloured decks of index cards and buckets of Sharpies. Indeed, this may still be the most effective way of running an example mapping session, but with remote working, distributed teams, and electronic project management tools, this approach is no longer generally suitable.

Traceability

One property that many organisations are looking for is requirements traceability – defined as "the ability to describe and follow the life of a requirement in both a forwards and backwards direction (i.e. from its origins, through its development and specification, to its subsequent deployment and use, and through periods of ongoing refinement and iteration in any of these phases)"

Simply put, traceability should be able to answer questions like:

- Has this requirement been satisfied?

- What requirements does this test case verify?

- Which versions of the product is this requirement available in?

- What requirement(s) required this code to be written?

The most typical demand for traceability comes from regulated industries, where external auditors demand evidence of compliance. However, traceability has far broader applicability than that. With the continuing shift towards continuous deployment, there’s a growing need for low overhead mechanisms that enable internal processes to automatically assess the fitness of software for release.

Example mapping already provides a link from user story to concrete example. Teams that are using a behaviour-driven development (BDD) approach will then formulate the concrete examples into business-readable, executable specifications that will guide development and provide long-lived, reliable, living documentation. Automated execution of the specifications extends traceability to test executions and product versions.

This is a significant advance when compared to the prevalent forms of requirements traceability in the industry today, such as spreadsheets or links in ALM tools. Even better, there is no overhead incurred. Every activity in the BDD approach delivers intrinsic value. Traceability comes as a secondary outcome.

If you're willing to help us understand your requirements traceability needs,

please fill out this very brief survey to participate.

Conclusion

The need for good requirements has existed since humankind first undertook projects that made use of more than a handful of people. Without good requirements, project outcomes are less likely to meet expectations, with negative consequences for all concerned. Manual quality processes are error-prone but do provide a level of confidence that we’re delivering what we have been asked for.

Modern software development organisations can no longer afford the rework that results from poor requirements, the delay that arises from manual quality processes, or the customer dissatisfaction caused by defective products. Example Mapping, automated tests, and requirements traceability combine to provide an effective solution that neither costs the earth nor taxes the brain.