[Extracted from BDD Books 2 - Formulation by Seb Rose & Gáspár Nagy]

Three practices of BDD

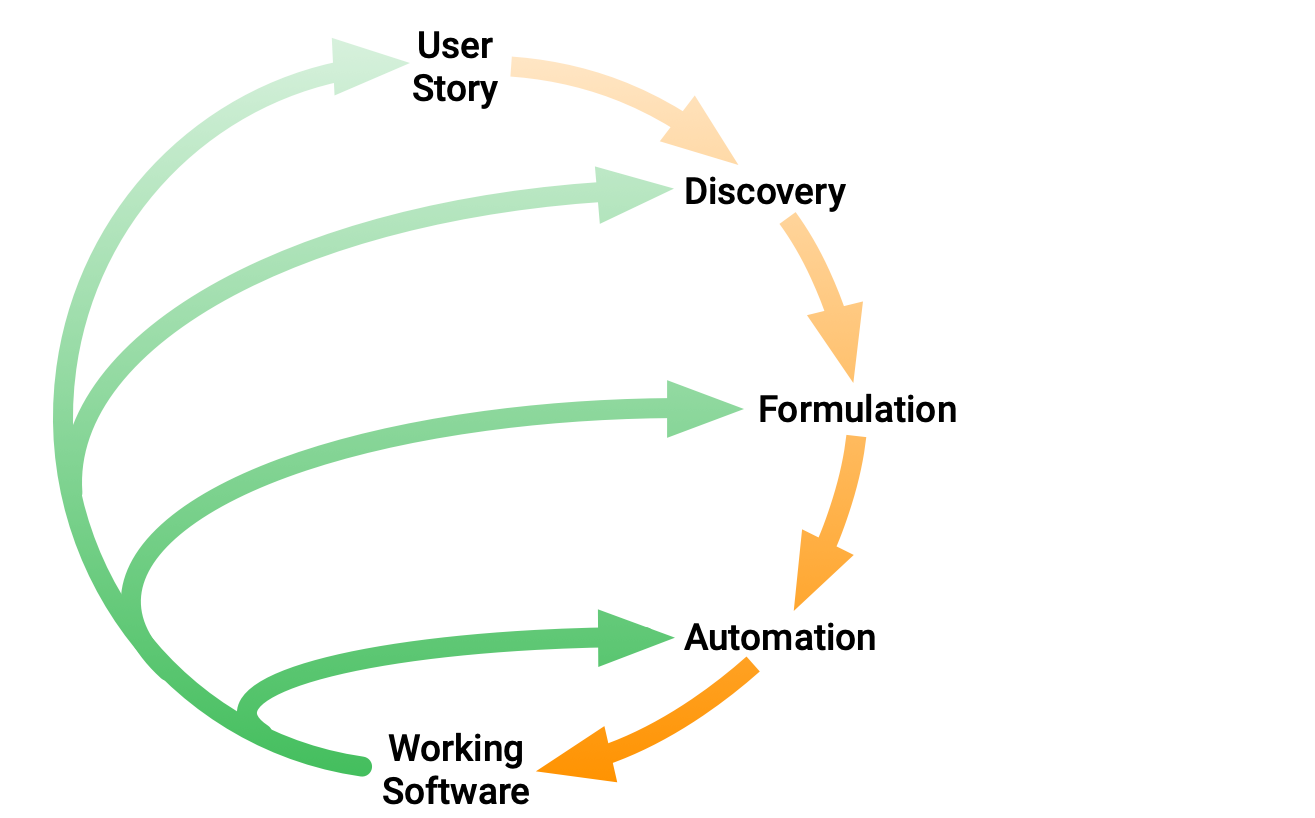

Over the past few years, there has been a growing recognition that BDD is an approach made up of three practices.

Three practices of BDD

Three practices of BDDDuring Discovery, the team will capture concrete examples of how the system is expected to behave. While doing this, they will also uncover important business terminology. Formulation is the process of transforming the concrete examples into business-readable specifications that will guide development and document the product for its whole lifetime.

Who should formulate the scenarios?

When considering who should actually formulate the concrete examples uncovered during Discovery, there are several questions that need to be answered:

- Why don't we formulate during the Discovery session?

- Shouldn't the whole team formulate together?

- Don't the PO/BAs own the specifications?

- Shouldn't the developers/testers focus on the implementation?

- Isn't it more efficient for one person do it?

Let's take a look at each of these questions.

Why don't we formulate during the Discovery session?

During Discovery we want to uncover misunderstandings and hidden assumptions. Our goal is to ensure that the whole team has a shared understanding of how a part of the system is intended to behave. To do this, we use concrete examples to facilitate fast, efficient communication between all participants.

To keep the communication fast and efficient, the concrete examples must be easy to capture. Formulation is a separate practice, with different goals and a more contemplative pace. Attempting to combine Discovery and Formulation will slow us down and limit the engagement of the team.

Shouldn't the whole team formulate together?

Since the scenarios will be written in a shared language (often called the ubiquitous language), it seems obvious that the whole team should be involved in writing them. However, we've found that most teams benefit from delegating formulation to a subset of the team – while maintaining collective ownership of the resulting scenarios.

The first reason to formulate with fewer people is for efficiency. If everyone in the team has an opinion on how an example should be written then the discussion can be very time consuming. Conversely, if some people don't engage in the discussion, then what benefit is there from having them involved?

Secondly, team members that don't participate in the formulation are expected to review the scenarios asynchronously. This gives them the time and space to read through the scenarios at their own pace and offer constructive feedback. Reviewing a scenario asynchronously also gives us confidence that it will be understood by people who weren't involved in the product's development.

Don't the PO/BAs own the specifications?

The goal of the product owner (PO) and business analyst (BA) is to share their business knowledge with the delivery team. This is essential for the delivery team to have enough context to make sensible decisions during development and testing. To confirm that this knowledge has been understood, there needs to be a feedback process.

When scenarios are written by members of the delivery team, they will then be reviewed by the PO/BA, which provides exactly the feedback that is needed. If the scenarios correctly reflect the concrete examples, and use appropriate business terminology, then we can be confident that the business and delivery sides of the team really do have a shared understanding.

The PO/BA is still accountable for the specifications – but the work of formulation is shared.

Shouldn't the developers/testers focus on the implementation?

There's a common misconception that the most valuable thing developers can do is write code. A similar misconception exists for the best use of a tester's time. In fact, to deliver value the delivery team must understand the business context of the requirement, so that they can make appropriate decisions.

Writing scenarios is an ideal way for developers and testers to demonstrate that they have a clear understanding of the business requirements and the business terminology.

Why can't just one person do it?

If formulation is more effective when done by a subset of the team, there's an argument that it might be most effective when done by just one person, rather than a pair. In our experience, all activities are improved when undertaken by a pair.

In the case of formulation, the tester/developer pair is ideal, because the developer is considering the automation aspect of the scenario, while the business-focus of the tester ensures the scenarios don't become technical.

Consider your own context

Your context may be different. Our suggestion of a developer/tester pair might not be acceptable in your organisation. Or your product owner might prefer to participate in writing scenarios, rather than just reviewing them. We have seen examples where other approaches to formulation work just fine, but in the vast majority of cases it's the developer/tester pair that works best.