User stories and BDD (part #2) - Discovery

This is the second in a series of articles digging into user stories, what they're used for, and how they interact with a BDD approach to software development. You could say that this is a story about user stories. And like every good story, there's a beginning, a middle, and an end. Welcome to the middle!

Previously...

In the last post we traced the origins of the user story. We saw that the term user story was used interchangeably with story, that stories were used as a placeholder for a conversation, and that this allowed us to defer detailed analysis. Now it's time to dive into the detailed analysis.

Last responsible moment

The reason we defer detailed analysis is to minimise waste – we don't want to work on features until we're reasonably sure that we're actually going to deliver them, and that work includes analysis. There's no value in having a detailed backlog that contains thousands of stories that we'll never have time to build.

The XP community approaches waste from another direction, with the concept of you aren't gonna need it (YAGNI). In a nutshell this tells us not to guess the future. Deliver only what you actually need today, not what you might need tomorrow – because you may never need it.

In Lean Software Development: An Agile Toolkit (2006), the Poppendiecks coined the phrase: the last responsible moment (LRM). This describes an approach to minimising waste based upon making decisions when "failing to make a decision eliminates an important alternative."

Accidental discovery

We want to defer making decisions until the last responsible moment because software development is a process of learning. We learn about the domain, what the customer needs, and the best way to use the available technology to deliver on that need. The more we learn, the better our decisions.

Learning something relevant after we've already made a decision is called accidental discovery. We made a decision believing we had sufficient knowledge, but we were surprised by an unknown unknown. The consequence of accidental discovery is usually rework (which is often costly), so our job is to minimise the risk of that happening.

Risks and uncertainties are the raw materials we work with every day. We'll never be able to remove all the risks, nor should we want to. As Lister and DeMarco put it so eloquently in Waltzing with Bears (2003) :

Deliberate discovery

As professionals we are paid to have answers. We feel deeply uncomfortable with uncertainty and will do almost anything to avoid having to admit to any level of ignorance. Rather than focus on what we know (and discreetly ignore what we're unsure of), we should actively seek out our areas of ignorance.

Daniel Terhorst-North proposed a thought experiment:

What if, instead of hoping nothing bad will happen this time, you assumed the following as fact:

- Several (pick a number) Unpredictable Bad Things will happen during your project.

- You cannot know in advance what those Bad Things will be. That’s what Unpredictable means.

- The Bad Things will materially impact delivery. That’s what Bad means.

To counter the constraint of "Unpredictable Bad Things happening", he suggests that we should invest effort to find out what "we are most critically ignorant of [and] reduce that ignorance – deliberately discovering enough to relieve the constraint."

By building deliberate discovery into our delivery process we are demonstrating our professional qualities – not admitting to incompetence. We are acting responsibly to minimise unnecessary risk and maximise the value that we deliver to our customer.

Example Mapping

Many agile teams will be familiar with backlog grooming/refinement meetings. The intention of these meetings is to refine our understanding of the stories on the backlog, but in my experience, they are often unstructured. Nor do they focus on uncovering what we, as a team, are ignorant of.

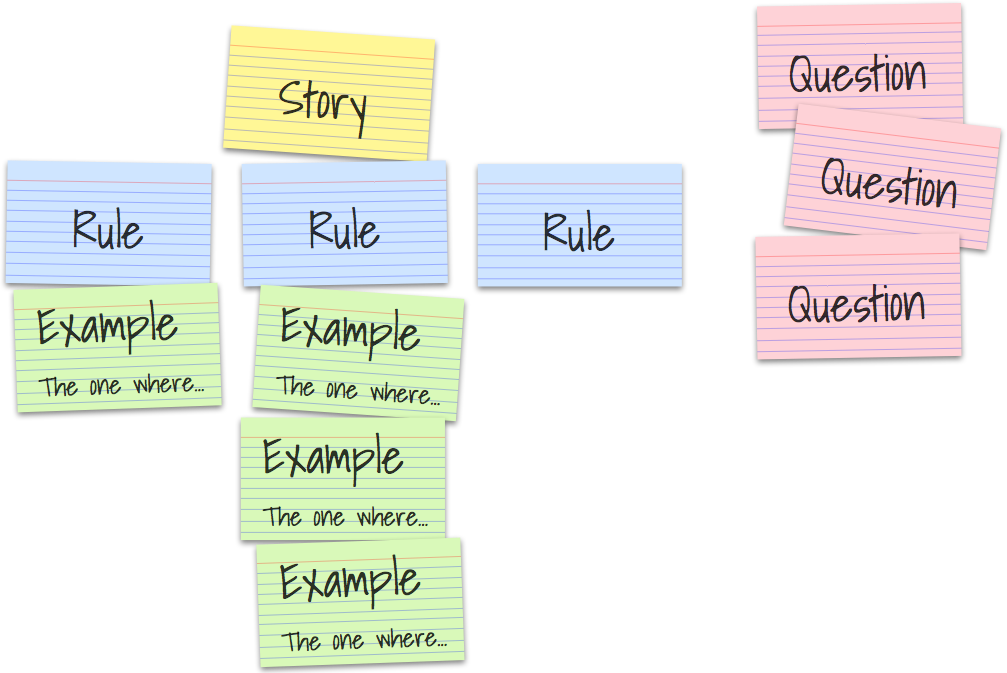

One of the most effective techniques for deliberate discovery is called Example Mapping – created and documented by my colleague, Matt Wynne. It's an extremely simple, yet extraordinarily powerful way of structuring collaboration between team members, harnessing diverse perspectives to approximate the wisdom of crowds.

https://cucumber.io/blog/bdd/example-mapping-introduction/

Example maps give us a visual indicator of how big a story is and how well we understand it. Once the story is well understood, we can use the example map to help the team split the story into manageable increments.

Stories all the way down

Stories start their life as placeholders for a conversation. As they get refined through the deliberate discovery process they become better understood, allowing us to decompose them into detailed small increments. Which we still call stories.

The transformation from placeholder for a conversation to detailed small increments is not well understood by agile practitioners. There's informal usage in the agile community of the term epic as a label that identifies a large user story, but epics and user stories can both be placeholders for a conversation.

Nor are detailed small increments equivalent to tasks. Tasks are used to organise the work needed to deliver a detailed small increment. Each task is "restricted to a single type of work" – such as programming, database design, or firewall configuration. Tasks, on their own, have no value whatsoever to your users. Each small increment, however, makes your product just a little bit more useful.

Same name, different purpose

By the time a piece of work is pulled onto the iteration backlog, the main purpose of the story is to aid planning and tracking. The title of each story is no longer all that important – the story is simply a container that carries the detailed requirements of the next small increment to be delivered.

Without the decomposition to detailed small increments that takes place during discovery, the stories will be too large. If there's one thing that hurts delivery teams more than anything else, it is inappropriately large stories. Nevertheless, most teams that I visit still work on stories that take weeks to deliver and this is still all too common in our industry.

Next time...

In this post, I've described how (and why) user stories change over time. Next time, I'm going to dive into the details of what "small" means in the context of stories – and why it matters.