The surprisingly inclusive benefits of mob programming

This experience report was written by Sal Freudenberg and Matt Wynne, first published on the Agile Alliance site after XP 2018 in Porto.

Mob-programming is a young practice, only starting to be embraced by agile teams. Remote mob programming even more so; it is rarely practiced and so far only poorly understood. This experience report describes the way the Cucumber team, who are fully remote, practice mob programming and the surprising benefits we have discovered.

1. Introduction

When Sal, recently diagnosed as autistic 1 joined the team at Cucumber for a day as part of her programming tour, she was really nervous.

Not only was she picking up programming again after more than a ten-year break, she was joining team full of super-experienced practitioners: most of them book authors or prodigious open-source contributors. Not only that, but they did mob programming so she would be taking her first steps back at the keyboard in front of the whole team! Not only that, they did their mobbing remotely, which clashed on a grand scale with some of the research that had come out of Sal’s PhD on pair programming. In fact, she felt sure that the lack of cues and dampened peripheral awareness from not working collocated would be a real issue to someone who struggles to pick up on the subtleties of interaction even in person.

This is the story of how Sal's experience on that first mobbing session ended with her completely changing her view on remote teams, along with some lessons we all learned about how remote mob programming can actually provide a more inclusive environment for all kinds of minds.

2. Background

Cucumber Limited emerged from the Cucumber open-source project, founded in August 2013 by Matt Wynne, Aslak Hellesøy (the creator of Cucumber) and Julien Biezemans. Today, the company has grown to around ten full-time staff, including Seb Rose (Cucumber-JVM contributor and author of The Cucumber for Java Book), Steve Tooke (Cucumber-Ruby contributor and co-author of The Cucumber Book) and this paper’s co-author, Sallyann Freudenberg.

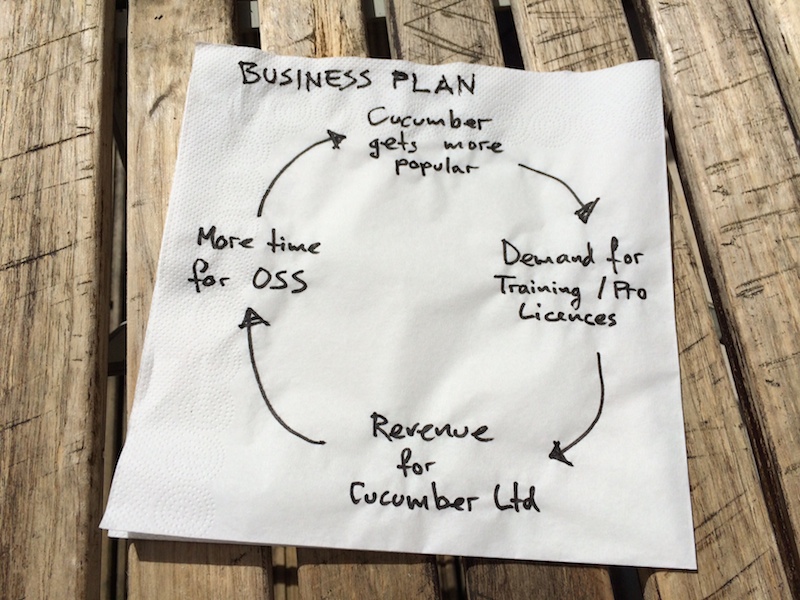

The company’s main business model has historically been to reinvest revenue from training and consulting work into time spent improving the open-source product, Cucumber. To supplement this revenue stream, the company has a long-term strategy to develop and launch a commercial enterprise collaboration tool, Cucumber Pro.

Founded by open-source programmers who were based all over the world, Cucumber Limited has always been a distributed company, with occasional in-person meetups in “pop-up” offices.

Cucumber is an acceptance-testing tool for agile teams, and almost everyone involved in the company comes from an extreme programming (XP) background. The founders earn money for the company by providing training and consulting in agile, lean and XP practices. Naturally, as they started to develop their own product, they used practices from agile, lean and XP. The team first experimented with Remote Mob Programming in late 2015 2 as they started a ground-up rewrite of what had been the first prototype of the Cucumber Pro product.

The practice became firmly established in early 2017 after learning from a tough period in late 2016 with work going on in parallel and insufficient communication between the pairs working on different problems. During a retrospective, the team agreed that there would always be a mob, working on the hardest problem.

Even at the time, as a fairly homogeneous group of 35-45 year-old white dads, the team had noticed how family-friendly remote mobbing was. As the company grew they wanted to make the development team more inclusive, to give them the broadest reach when recruiting new members and to enjoy the other well-documented benefits that more diverse teams have.

The team had some concerns 3 that the combination of their level of experience, and the remote working could be a barrier to adding new team members.

Enter Sal, a long-term friend of the Cucumber team and experienced agile/lean consultant, about to embark on a Coding Tour 4. Despite having a pretty technical background (she once wrote real-time process control middleware for nuclear power stations), Sal’s career has long steered away from doing a technical role. In fact, it was well over ten years since she had written any commercial code at all, and since then she had only tinkered on small hobbies with her kids.

The purpose of Sal’s coding tour was twofold: To see how easy (or hard) it is to start coding again as a returner, and hopefully via blogging about the experience, to encourage others (particularly women) who have been out of the industry for quite some time that it is still possible to return to a technical role. Sal felt sure that there must be many talented technical women out there who have left the industry, perhaps to start a family or take a career break, and feel both intimidated by how much things have changed and ill-equipped to catch back up.

Sal has a PhD in the Psychology of Collaborative Software Development, so part of the idea was that she might provide insights as an outsider for teams that she visited. Sal’s PhD focused on pair programmers and how they interacted, and some of her findings were about the benefits of colocation - fluid re-pairing, peripheral awareness and re-appropriating physical artifacts to assist with the collaboration. She was interested to see whether remote mobbing can really work, and if so, how.

Sal had also recently realised that she is autistic. Like many autistic women she is excellent at masking, however she struggles with (and gets exhausted by) prolonged and intensive social interaction, finds loud and brightly lit spaces overwhelming, misses social cues and is both capable of very intense concentration whilst also being easily distracted. Sal’s autism also allows her to get deeply focused on details and to see options and information that others might not pick up on. She is not frightened of starting difficult conversations. Since her diagnosis, Sal has busily been learning how to embrace her autism and both be kinder to herself and be more open about her differences both at home and at work.

How would her new found knowledge and self-awareness change her experience of technical work and what changes would the team need to make? Everyone was very excited to see what they would learn.

3. Getting Started

In preparation for Sal’s first mobbing session she had two familiarisation sessions to learn about the product in development and discuss the development tools and process. These sessions were requested by Sal rather than required by the Cucumber team in any way. In retrospect, these sessions were invaluable in helping to understand the overarching architecture, the approach that had been taken (CQRS / event sourcing 5) and also to help Sal to feel a little more comfortable with remote interaction, the tools used (Zoom and Slack). At the end of each session Sal drew a picture of her understanding of the architecture so far which was used for discussion and to draw out further questions / see where she might have misinterpreted or misunderstood something.

As timing would have it, Sal’s first mobbing session with the team wasn’t, in fact, remote. The Cucumber team meet in person every month or so, and some of these sessions are allocated as Developer meetups. It just so happened that there was one about to take place in Wavre, Belgium. The team invited Sal along.

Here’s a story Sal tells that shows how that first mobbing session felt:

“Imagine if you can that you used to be a reasonably good singer in school. You maybe hadn’t sung for quite a while, years now you come to think of it, but you used to be quite good. Just recently you have wondered about singing again and have enrolled yourself in a one-day singing workshop, imagining it will be full of people just like you.

“The day comes, and you arrive at the workshop happily humming to yourself. For the first exercise everyone is going to take it in turns to sing for ten minutes. You are last in the line. While each person ahead of you takes their turn you realise with a sinking feeling that everyone else there is a professional opera singer. Not only that but they have invented some kind of new genre of opera mixed with jazz. Not only that, but they have created their own new notation for this genre that you have no idea how to read, and to top it off, they are all amazing.

“Eventually they turn smilingly to face you and say: “Your turn”. You gulp, remembering all those times before where you have maybe been socially inept, but there’s no escape…so you dive in. It’s clear you are very very far from any kind of expert, but you know what, these folks are really encouraging. They smile at you. They hum the notes for you when you are off-key. They applaud when you finish and they mean it. You say “I’m so sorry, I haven’t done this for ages” and they say “You did just fine, and you helped us realise that this new notation is really inaccessible, we should definitely tweak it”. The blood slowly returns to your face. You take a deep breath. Maybe this IS going to be OK after all”.

Mobbing first in person may well have made the transition to remote mobbing more seamless. Sal has long advocated that remote teams first work colocated if they can, to iron out any tricky issues which may be harder to address remotely. Through mobbing in person, we provided time to get accustomed not only to each other, but to some of the tools the team commonly use when mobbing. We agreed on using WebStorm as an IDE and used that during the sessions; we used a timer to ensure that each member of the mob was only in the driver’s seat for ten minutes at a time; we used the same general process and tools as we would when mobbing.

4. Mobbing Remotely

The team currently uses Zoom to host the remote mobbing sessions. The driver shares their screen. A Slack channel is also used as a back-channel for sharing information, code, links, etc.

The ten-minute timer not only ensures everyone takes a turn driving, and stops that session of driving from being too daunting, it also keeps us honest about baby steps. The need to commit and push code at the end of ten-minutes so that the next driver can pull it down to work on forces us to work in small, bite-sized chunks in a very disciplined way. Of course, sometimes we cheat (if we are just about to finish off something when the timer goes and need a few more minutes to get it into a committable state), but mostly we do not.

One fabulous side-effect of mobbing is the fact that a team member can completely tailor their own physical environment and even change it around depending on their needs that day: the ability to sit in one’s favourite chair, have just the right level of lighting, turn the volume up and down, have fiddle toys or calming activities to hand, have access to favourite and suitable food and drinks.

*pinches self" Did I really just spend a couple of hours remoting co-facilitating a workshop (from home) with @tooky where we remote mobbed writing a scene from a Portuguese crime thriller? #thatescalatedfast #madlife #somuchfun #xp2018 //cc @eegrove

— Sallyann Freudenberg (@SalFreudenberg) May 25, 2018

Here’s Sal’s perspective on this:

“The possibility to create a sensory environment uniquely tailored to my needs that day is a wonderful luxury I have never been afforded in an office. The accompanying feeling of safety helps to compensate on the days I am feeling nervous about joining the mob or struggling to focus.

“In addition, it is supportive of a level of social interaction that feels more manageable - it is completely acceptable to turn off or hide people’s faces, although in practice I rarely do. I find the option comforting, and it is fine to leave the mob if the interaction feels too intense or prolonged. Of course, there is no pressure to be social during breaks either - I can just turn off the screen and have silent, alone time”.

Timings have flex, whilst the mob is “alive” from around 8.30 until maybe 5pm, the participants join and leave as and when they need or desire to do so. Not only does this help with social exhaustion, it creates an environment where it is OK to hop on the mob a little later so you can drop the kids at school or leave early for a meeting. Sal often goes for a run in the morning which she finds calming and helps her to focus for the day.

We believe there is a hidden benefit in this too, as each time someone joins, the mob is forced to depart from the detailed world of writing code in order to explain what they are trying to achieve from a more strategic product development perspective.

4.1 Puzzles we still have

Of course we are far from perfect and there are still a number puzzles to consider:

On occasion, although less and less often as time passes, Sal feels that she is slowing the mob down. There is often a feeling of urgency to get things done and Sal is sometimes self-conscious that her lack of prowess with short-cuts or need to ask for clarification when driving might feel excruciatingly slow to the rest of the team. Of course, Sal has never been on a mob without a Sal, so does not actually know whether this is true. Sometimes, far from being a hindrance, the team finds Sal’s questioning beneficial - they have worked together on the same code-base for a long time now, and have got out of the habit of questioning the way they do some things.

Also, Sal’s novice eyes have helped the team to realise when the functionality is too obfuscated or the architecture too difficult to interpret. The team has used this information to decide what to refactor. Sal sometimes likens herself to a canary down a mine - rather than passing out when the air is difficult to breathe as a warning for the miners, Sal “faints” when the code is too complicated to understand so the team are aware it might need simplifying.

From a personal perspective, part of Sal’s neurology is that she finds it almost impossible to multitask. When focused on coding, the other members of the mob appear able to keep track of Slack too, trading ideas, tips, snippets of code etc in a dedicated channel without becoming quite as absorbed by this other channel.

Possibly because Sal is hyper-focused or possibly because she is only working on a single screen (two screens are not only unavailable but seem like it would be overwhelming), Sal is unable to track the Slack channel and concentrate on the code at the same time - and this is the case whether she is driving or not.

As such, on occasions, Sal has missed some helpful information, comment, guidance or example code that would have been of use whereas the other members of the mob have assumed that she has seen it. In fact, when she has tried to take a look at Slack during a mobbing session she just gets completely distracted by it and forgets what the mob were doing with the code at all. During the writing of this report, it has become clear that other members of the team also find Slack somewhat busy and distracting as a team back-channel whilst mobbing.

One whole-mob puzzle is rabbit-holing or, if you prefer, yak shaving. It is so easy to drill down so deeply when solving a particular problem that one gets side-tracked and loses sight of doing the simplest thing that will work. Not only that, but when working in a mob, it feels as if group polarisation comes into play 6 and we inadvertently collude to give each other permission to do this. At the end of the day, we are all developers who love to solve problems.

Sometimes this joy means we stray from the task at hand. There are two things that help - one is the timer keeping us honest, the other is something that we have come to lovingly refer to as the ‘yak map’. We use the MindMup 7 tool to draw and update a mind-map of our problem solving as we go. Sometimes each time we rotate driver, sometimes more often, we try to revisit this yak map to tick off which parts of the problem we have already completed and to focus on doing the right part next. We are not always as stringent with this as we might be, but it is a useful tool and one that I feel we would do well to incorporate into every mobbing session we do.

Drawing is another sticking point. Sometimes when we pull back away from the code and need to talk at a higher level of abstraction we want to use diagrams to assist the conversation. We have yet to find the best tool to use for this and often resort to one person drawing on their whiteboard or even a piece of paper with their webcam capturing it as best it can. For a team that is used to collaborating together and co-evolving artifact, the inability to collaborate in real time on diagrams and other informal external representations can feel quite restrictive.

Another puzzle we have is around retrospectives. While the ebb and flow of people in and out of the mob feels okay for keeping a shared consciousness at work on the code itself, we’ve found retrospective conversations are less effective unless everybody’s there. We’ve probably found most success with short, daily retrospectives, but it’s easy to slip out of the discipline of doing these when the code lures you into fixing that one last test. Like the whiteboard, it feels like we still haven’t found the right medium for running our retrospectives remotely.

4.2 What we learned

The first thing that we learned is that we all really enjoy working together. So much so that Sal has now joined the Cucumber team permanently as a Director and co-owner of the business.

Perhaps more surprisingly, we have learned that rather than being a cutting edge, expert-level practice, mob programming is surprisingly inclusive. Done right, it can provide a safe and nurturing environment for the fledgling programming skills of novice programmers (or in this case returners).

Not only this, remote mobbing offers significantly more support and flex for family life or other interests. Most unexpectedly of all, the ability to uniquely tailor a physical environment that is right for you to work in would be almost impossible to achieve in a traditional work environment. Couple this with a level of optionality about level and duration of social that is also difficult to achieve in an office, and we believe you have a blueprint for maximising inclusivity for the neurodivergent team member(s).

Sal and many others have already written and spoken widely about the benefits of a neurodiverse development team (9, 10) so we will not repeat the case here, however we believe that remote mobbing may be a powerful way to unlock the potential of your neurodiverse team.

5. Acknowledgements

We’d like to thank Woody Zuill and Llewellyn Falco for their work to popularise mob programming. The rest of the Cucumber Team: Seb Rose, Steve Tooke, Julien Biezemans, Aslak Hellesøy and Romain Gerard for creating such a wonderful learning environment. Finally thanks to our Shepherd Johanna Rothman for making sure this paper came together.