Cucumber anti-patterns (part #2)

If you haven't read our first blog post already, start by doing that over here. Some of the examples we use in the first post will be referenced below.

Practicing Cucumber and BDD is often tricky for new teams. There's plenty of information out there, but who to believe? Core to our business is helping teams around the world implement BDD practices into production. In the past few years we've helped hundreds of teams do this successfully through our in-house and online training.

This post is an edited conversation between Cucumber's Steve Tooke, Aslak Hellesøy and Matt Wynne.

Let's begin!

Testing through the UI

Testing through the user interface can be bad for a number of reasons. First of all, UIs tend to change a lot more than the underlying business logic, new trends are appearing all the time and you keep trying out different things to please your users. If you keep changing the UI, your tests are going to break and you’re going to have to dedicate a lot of time keeping them up to date.

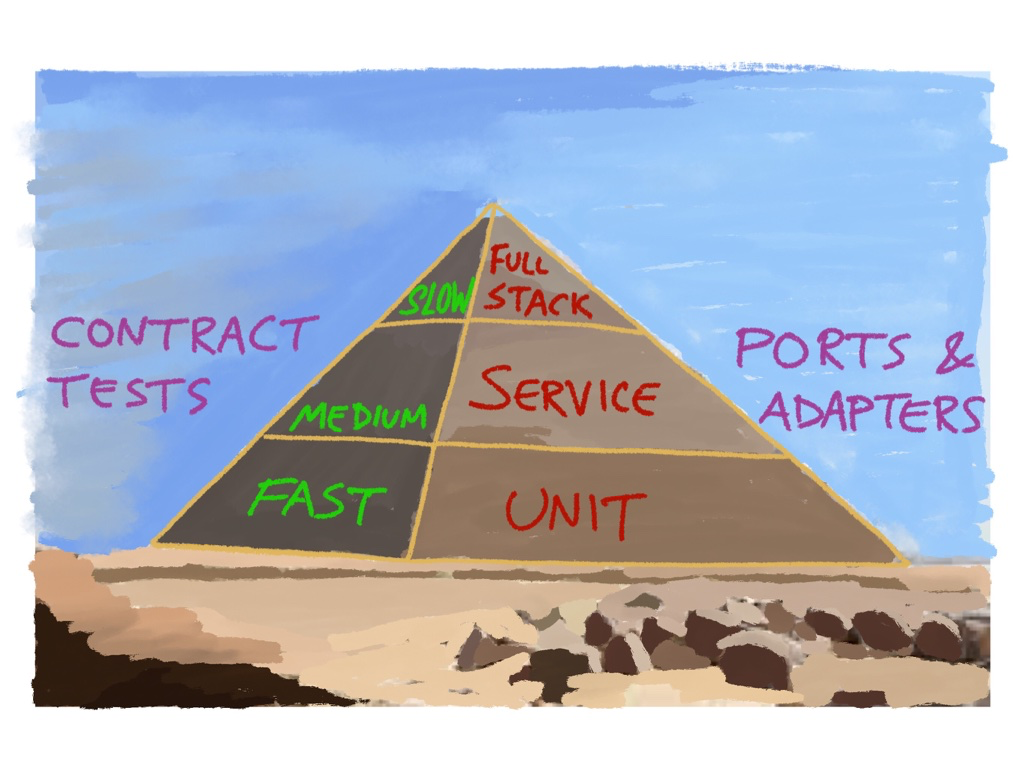

They are also incredibly slow. The only way to test them is through the entire user interface all the way down through your domain logic, and up to the database, and external services, and back. And so it’s just very cumbersome. So when you write your Gherkin in this way, you are stuck forever at the top of the testing pyramid. There's no way for you to go further down and test things underneath the UI, which is less brittle and a lot faster.

It also acts as really poor documentation. Let say that it was about the thing that we talked in the last post, where you withdraw money and you want to make sure that you see that withdrawal in your list of recent transactions; if you describe this using a different terminology, which is all about buttons and links and fields and tables, you're not really explaining the business rule. So it just acts as really, really poor documentation.

Dan North's made the point before that you don't learn your domain language. So using that language of clicking buttons and filling things in is just of a generic domain language of any user interface. But if you say what is it you're trying to achieve - like when I log in, or when I check my balance, or when I print a statement - you're having to use nouns and verbs that are from your domain, and therefore those nouns and verbs are going to be words that you're going to be able to use deeper down in the code. So you're starting to discover the language of your domain rather than just using generic words from any domain.

And again, in order to be able to do that, you need to get into the habit of writing these things before you write the code and not after.

Scenarios that use “I” as in the personal pronoun

Most useful systems or most interesting systems need to exhibit behavior that is seen by multiple actors. So if you're building a social network you need to be able to have; Aslak tweeted a message and Steve, who is following him, sees the message but Matt, who is not following him, does not see the message. So if you start talking about when I tweet blah blah... it's like, "Who are you? Are you Aslak or Steve or Matt?"

We all do it, but the scenarios tend to be richer and more accurate when you avoid the personal pronoun.

Keeping noisy scenarios

Sometimes documenting boring scenarios like, "Given my bank account is empty, when I check my balance, then the balance should be zero" are useful on day one of the project, but you can end up with a lot of noise in your documentation if that's all that you're documenting.

Most of the time, these kinds of tests that are just obvious. They're just there because you needed a full stack test to help you drive out your first iteration of the implementation.

Try and delete scenarios because quite often that basic functionality will be covered by others that you write later. You can either just delete those old ones that are now a bit daft, or rephrase them into something slightly more valuable. And if you can't, just get rid of them.

Overuse of scenario outlines

Overuse of scenario outlines tends to result in lots of scenarios, because it's really easy to add just another scenario. And this is one of the main things that leads to slow Cucumber tests. Here’s the rule of thumb we practice: if you're using scenario outlines, don't do it with a UI test or anything that's slow. That of course requires you or the developers to build the system in such a way that it is testable without going through the UI. If you'd like to learn more about this, watch this talk.

Developers or testers who write their scenarios without talking to business people

When we go and visit teams we often see example data that is really dry and dull, like "Given user one has an expired credit card and user two has a credit card that is valid, when user one checks their balance, and it's just user one and user two are just..." You have come up with those example names because you can't think of a more realistic example, and that kind of thing usually happens because you haven't had that dialogue beforehand.

If that's the cae, you're missing out on a whole potential of extra levels of communication. Jenny Martin talked at CukeUp! last year about how they use the same examples, right the way through, from their story mapping sessions and UX storyboarding and stuff, all the way through to their unit tests. The same characters appear and reappear, the same prototypical users appear and reappear, and the same situations and scenarios appear and reappear. The dry and dull data is a result of the team thinking about these as tests rather than thinking about them as a communication mechanism.

No clear separation between Given, When, and Then

We see a lot of people struggle with the difference between them because to Cucumber, there is no difference. The only reason there is "Given, When, Then" is to make it easier for people to write something that reads better. So what we say is "Given" is your context, "When" is the action or the event, and "Then" is the outcome or expected outcome. Think of "Given" as the past, "When" is the present, and "Then" as the near future.

And the metaphor to explain this is going to the theatre. So the "Given" is imagine you're sitting in your chair, assuming you had a seat at the theatre, and the curtains are drawn. And what's happening is stage workers are on that stage behind the curtains. You can't see them. They're moving furniture about and maybe the actors are walking onto the stage, and they're preparing themselves for the act. That's the "Given". It's putting all of the right things in the right spot. And then when the curtains are drawn aside and the act starts, that's your "When". There's one important thing that happens that causes something else to happen. And that something else to happen is the outcome. So "Given" all of the actors are walking onto the stage, which means setting up stuff in your database, creating some objects, maybe navigating through the initial web page. "When" is for triggering the important event, and "Then" is for observing the expected outcome. And it's not complicated but people tend to mix them up a lot, and that just makes it hard to reason about them.

High-level and vague scenarios

So we've talked already about the end of the spectrum where there's too much detail, where the scenario is boring, and even maybe distracting to read because it's just got loads and loads of irrelevant incidental detail in it. But the other end of the spectrum is that you can't really trust the scenario, or you can't tell what it would actually do if you run it.

For example:

Given I have an account

When I withdraw some money

Then the balance should be the original balance minus the amount withdrawn

There's no concrete value in there. It doesn't say what my balance was, it didn't say how much I withdrew, it’s basically expressing the business rule, but using the "Given, When, Then" format.

And the extreme example of that, where you're so abstract, is where you just say, "Given the system is turned on, when I use it, then it works perfectly!

Sometimes in a untestable place where a team are just getting used to using Gherkin, but they haven't actually done any automation yet, they're writing scenarios, but they're really just using Gherkin as a way of expressing business rules rather than being concrete. They've just taken the lever a little bit too far towards abstract. It's arguably a bit better than too much detail, but finding that balance between too much detail and not enough detail is a bit of an art rather than a science. And I think teams shouldn't get too hung up about getting it perfect, but it's definitely a problem when there's not enough detail and you can't really tell what's going to happen under the hood.

This tends to be more common when product owners or business analysts write the scenarios alone in their office in JIRA, because they are not programmers and testers so they don't know the implications of writing it in that form.