BDD is a centered community rather than a bounded community

Dan North mentioned at one point in the CukeUp 2015 panel yesterday the notion in theology of a community being a "bounded set." Since Tom Stuart had been gracious enough to invite me to participate in the panel, towards the end of the session I joined the panel so I could expand on Dan's comment. I pointed out that the same theology also talks about the notion of a community being a "centered set." To me, this is what BDD really is: A centered set, rather than a bounded set. In other words, _BDD is a centered community, rather than a bounded community.

I want to be clear what I meant by bounded vs. centered set as it applies to a community when I proposed it in the CukeUp 2015 panel. These terms originated in a theological context with the writings of anthropologist and missiologist Paul Hiebert, in terms of what makes a person a Christian. I'm going to quote and adapt a significant amount of the content from his original article in what follows to make it relevant for those without a background or interest in theology. Before I do that though, first a little background is in order.

CukeUp 2015

The CukeUp 2015 conference at Skills Matter in London culminated yesterday in an wonderful panel discussion about what BDD actually is, organized and facilitated by Tom Stuart. I highly recommend anyone interested in current thinking in BDD watch the video posted by Skills Matter.

It seemed clear to me from the sentiments expressed in the session that focusing on boundaries and exclusion is not what the BDD community has ever been about. BDD is a community with values and principles at the center that promotes a certain growing body of knowledge and cloud of practices.

But there is no interest the BDD community in adopting a bounded set approach, and staying static by "locking down" the body of knowledge or cloud of practices that currently makes up BDD. Rather, the BDD community wants, and needs, to continue challenging the status quo and incorporating new learning and practices as they reveal themselves in the future.

Bounded sets

In his 1978 article, Hiebert notes that many of our words refer to bounded sets: "apples," "oranges," "pencils," and "pens," for instance.1 What is a bounded set? How does our mind form it? In creating a bounded set our mind puts together things that share some common characteristics. "Apples," for example, are objects that are "the firm fleshy somewhat round fruit of a Rosaceous tree. They are usually red, yellow or green and are eaten raw or cooked."

Bounded sets have certain structural characteristics — that is, they force us to look at things in a certain way. Let us use the category "apples" to illustrate some of these:

a. The category is created by listing the essential characteristics that an object must have to be within the set. For example, an apple is (1) a kind of "fruit" that is (2) firm, (3) fleshy, (4) somewhat round, and so on. Any fruit that meets these requirements (assuming we have an adequate definition) is an "apple."

b. The category is defined by a clear boundary. A fruit is either an apple or it is not. It cannot be 70% apple and 30% pear. Most of the effort in defining the category is spent on defining and maintaining the boundary. In other words, not only must we say what an "apple" is, we must also clearly differentiate it from "oranges," "pears," and other similar objects that are not "apples."

c. Objects within a bounded set are uniform in their essential characteristics. All apples are 100% apple. One is not more apple than another. Either a fruit is an apple or it is not. There may be different sizes, shapes, and varieties, but they are all the same in that they are all apples. There is no variation implicit within the structuring of the category.

d. Bounded sets are static sets. If a fruit is an apple, it remains an apple whether it is green, ripe, or rotten. The only change occurs when an apple ceases to be an apple (e.g., being eaten), or when something like an orange is turned into an apple (something we cannot do). The big question, therefore, is whether an object is inside or outside the category. Once it is within, there can be no change in its categorical status.

What if BDD was a bounded set?

What happens to our concept of "BDD" if we define it in terms of a bounded set? If we use the above characteristics of a bounded set we probably come up with something like the following:

a. We would define "BDD" in terms of a set of essential or definitive characteristics. These characteristics, such as perhaps collaborative specification by example, test-first automation, feature injection, red-green-refactor (TDD), would be non-negotiable for people doing BDD.

b. We would make a clear distinction between what is "BDD" and what is not. There is no place in between. Moreover, maintaining this boundary would be critical to the maintenance of the category of BDD. Therefore it would be essential we determine who is doing BDD and who is not, and to keep the two sharply differentiated. We would want to make sure to include those who are truly doing BDD and to exclude from the community those who claim to be but are not. If BDD was to be a bounded set, to have an unclear boundary would be to undermine the very concept of BDD itself.

c. We would view all "BDD practitioners" as essentially the same. There would be experienced BDD practitioners and beginners, but all are doing BDD, since they are within the boundary. Homogeneity within the community in terms of belief and practices would be the norm and the goal.

If we think of BDD as a bounded set, we must decide what are the definitive characteristics that set a BDD practitioner apart from a non-BDD practitioner. We may do so in terms of belief in certain essential "truths" about BDD, or strict adherence to certain essential BDD "practices."

BDD, as understood by leaders within the community, is clearly NOT a bounded set. Rather, it is a centered set. Let's see what we mean by that.

Centered sets

There are other ways to form mental categories. Hiebert says a second way is to form centered sets. A centered set has the following characteristics:

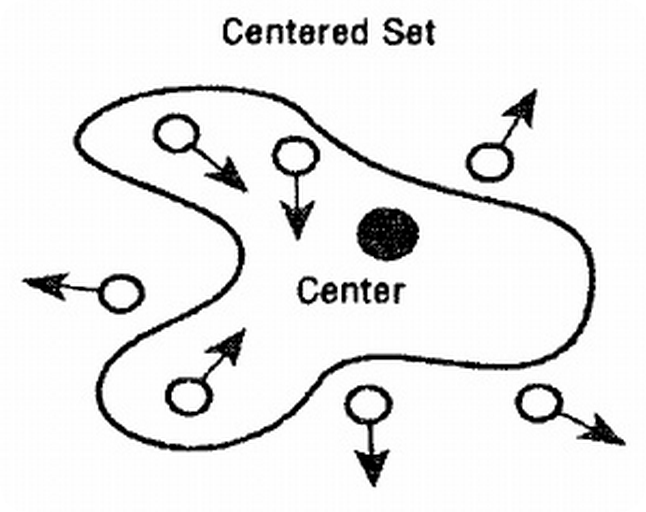

a. It is created by defining a center, and the relationship of things to that center. Some things may be far from the center, but they are moving towards the center, therefore, they are part of the centered set. On the other hand, some objects may be near the center but are moving away from it, so they are not a part of the set. The set is made up of all objects moving towards the center.

b. While the centered set does not place the primary focus on the boundary, there is a clear division between things moving in and those moving out. An object either belongs to a set or it does not. The set focuses upon the center and the boundary emerges when the center and the movement of the objects has been defined. There is no great need to maintain the boundary in order to maintain the set. The boundary is not the focus so long as the center is clear.

c. Centered sets reflect variation within a category. While there is a clear distinction between things moving in and those moving out, the objects within the set are not categorically uniform. Some may be near the center and others far from it, even though all are moving towards the center. Each object must be considered individually. It is not reduced to a single common uniformity within the category.

d. Centered sets are dynamic sets. Two types of movements are essential parts of their structure. First, it is possible to change direction — to turn from moving away to moving towards the center, from being outside to being inside the set. Second, because all objects are seen in constant motion, they are moving, fast or slowly, towards or away from the center. Something is always happening to an object. It is never static.

Illustrations of centered sets are harder to come by in English, since English tends to see the world largely in terms of bounded sets. One example is a magnetic field in which particles are in motion. Electrons are those particles which are drawn towards the positive magnetic pole, and protons are those attracted by the negative pole. The diagram here is another way of visualizing a centered set.2

BDD as a centered set

In contrast to a bounded set, how does the concept "BDD" look defined as a centered set as I propose?

a. A BDD practitioner is be defined in terms of the center — in terms of the principles, values and goals that the BDD community holds to be central. These principles, values and goals were enumerated quite clearly by Dan North and others during the panel session and are spelled out in other places (Dan's original article about BDD in Better Software was published in 2006 and still applies today). From the nature of the centered set, it should be clear that it is possible that there are those near the center who know a great deal about BDD, but who are moving away from the center. On the other hand there are those who are at a distance — who know little about BDD because they are just starting to learn it — but they are still BDD practitioners.

b. There is a clear division between being doing BDD and not doing BDD. The boundary is there. To pick an extreme example, I mentioned on the panel that a team doing waterfall (serial lifecycle phase gate) development with no collaboration between roles, not using examples, and doing no test automation at all could not be said to be doing BDD. But with a centered set there is less stress on maintaining the boundary in order to preserve the existence and purity of the category, the BDD community. There is also no need to play boundary games and institutionally exclude those who are not truly part of the BDD community. Rather, the focus is on the center and of pointing people to that center. Inclusion, rather than exclusion, is the name of the BDD game.

c. There is a recognition of variation among the BDD community. Some are closer to the BDD values in their knowledge and practice, others have only a little knowledge and need to grow. But - whether novice or expert or somewhere in between - all are doing BDD, and are called to continuously seek to improve and grow in their understanding and practice of delivering value early and often.

Being a centered set, growth thus is an essential part of practicing BDD. When a team begins doing BDD, they begin a journey and should strive to continue to move towards the center. There is no static state. Learning BDD is not the end, it is the beginning. We need good BDD education, mentoring and coaching to teach BDD to the many beginners who will join the community in the years to come, but we must also think about the need to continuously improve and inspire novices to move beyond following recipes and so-called "best practices" and experiment with tailoring BDD to their unique context.

I submit that the agile community in general should also be considered a centered set, with the agile manifesto as the central value statement for the movement. Whether BDD, or agile in general, being a centered community rather than a bounded one must involve always seeking to not only uphold but also increase the gravitational pull of the values at the center.

This blog post was originally posted on Paul Rayner's blog.