There are four subsections to this article.

- TDD

- BDD

- Contradiction.

- xDD

We’ll start off with an introduction to TDD. I’ll go through that quite quickly because I guess most of you reading this are already doing that. Then, I’ll spend a little more time on BDD and then deal with the contradictions between the two, before getting slightly more philosophical with xDD.

What is TDD?

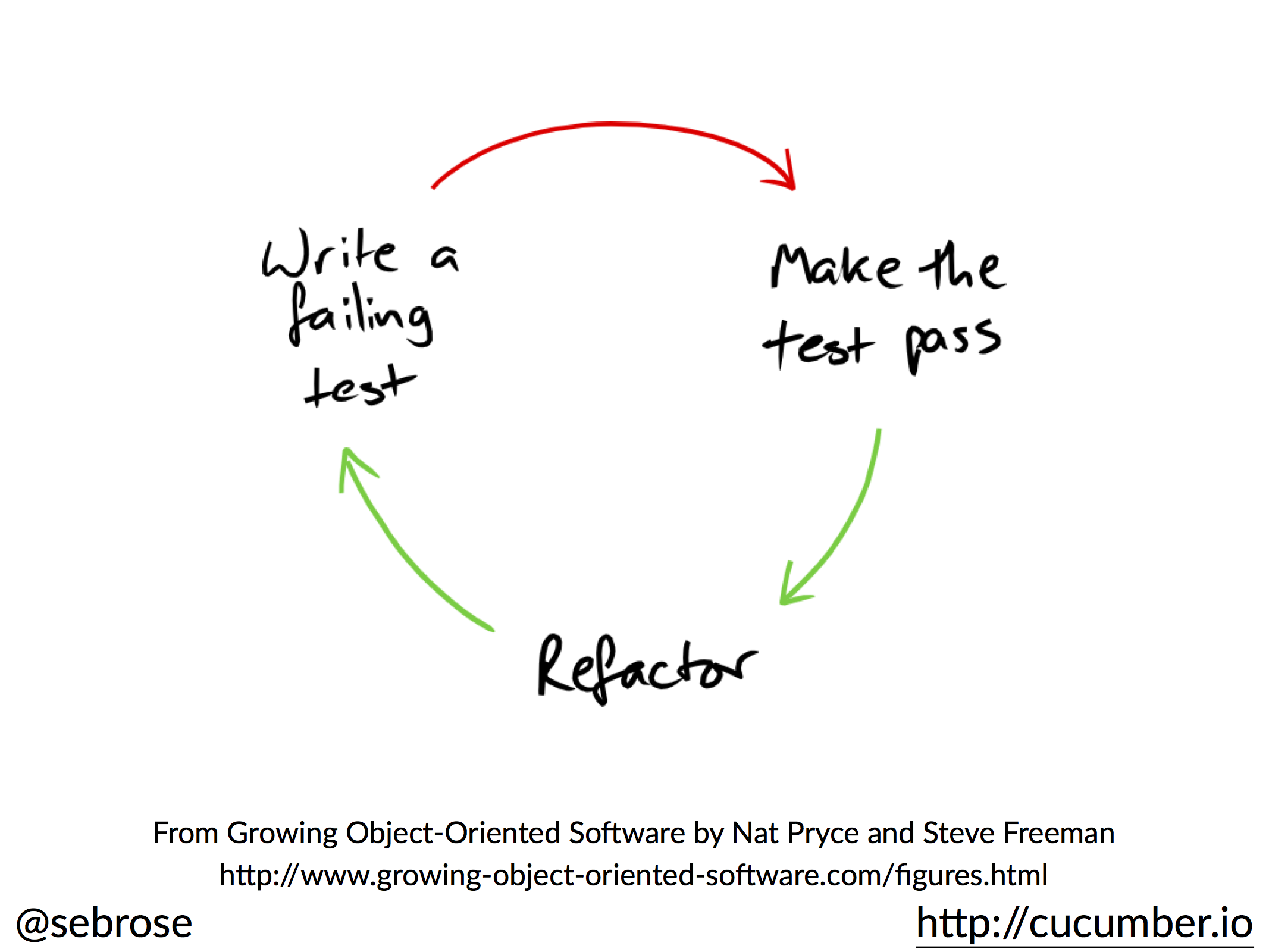

This is the classic TDD cycle, popularized in Nat Pryce and Steve Freeman’s book ‘Growing Object-Oriented Software, Guided by Tests’. It’s generally described as ‘write a failing test’ and then make the test pass and then refactor; you continue in this loop. This is the TDD cycle – it’s really simple. It’s got three little statements; it’s got coloured arrows that go between them. But within that, there’s a lot of complexity or at least a lot of nuance.

Here is another way of thinking about it. While ‘write a failing test’ is procedurally correct, it’s also rather confusing because that’s not what you’re attempting to do; the idea is not to write a failing test. What you’re trying to do is imagine what the next step you want to make is to evolve the implementation that you need to deliver value. It’s quite often rewritten as ‘writing the next specification’. Essentially, your next test is your next specification of how the software should behave and because you haven’t done that yet, it’s going to fail but you’re not there writing a failing test.

The second step is to make it pass quickly. The intention is not to design everything perfectly; it’s to get that test passing. Your collection of tests go from failing to all passing and now that all of your tests are passing, it’s safe to refactor. The intention here is not to get the best design; it’s to get them all to green quickly, because now they’re all green, you can look at them and go ‘how do I want to improve this design?’ and you can safely improve the design through the refactoring.

The third thing is refactoring. The refactor loop in Nat and Steve’s book is actually a cycle. You can draw it many other ways, but the idea is you don’t just go in and refactor and you’re done; you go in, you look and see what you would like to change and change it. You make sure the test is still green and you look at it again and say ‘is there another change that I want to do?’ or ‘has that refactoring introduced another thing that I want to do?’. This is a multi-process in itself; it’s not a single step.

Those are the three phases of TDD.

One thing to dwell on very briefly is the word ‘refactor’ because when I talk to developers ‘refactor’ is often misunderstood. When you’re refactoring, you are not changing the behaviour of the code. You never refactor to add a new piece of functionality. You might refactor to get the codebase into a state where you want it to be so that you can add a new piece of functionality but:

refactoring, by definition, does not alter the externally observable behaviour of the code.

What is BDD?

TDD as I explained quite quickly is quite contained.

BDD, however, is extremely uncontained; it’s sort of weird. No one is quite sure what it means. Matt Wynne who works with me at Cucumber Limited and has been working BDD for a while, has tried to distill its essence. He’s come up with this sentence.

“BDD practitioners explore, discover, define, then drive out the desired behaviour of software using conversations, concrete examples, and automated tests.”

There are a lot of words on the page and actually, if you squint a little bit, it goes all blurry. There are some interesting things in here but essentially, BDD is a 3-level approach.

The first is to get developers, testers and people from the business to talk to each other. That is the beginning of BDD. Anyone who thinks "we’re doing BDD because we use ‘Given’, ‘When’, ‘Then’" often aren't. ‘Given’, ‘When’, ‘Then’ has nothing to do with BDD. BDD stands for Behaviour-Driven Development and the real intent is to try and work out what your customer or business wants from the software before you start working on it. The first way of doing this is to actually collaborate with those people.

The second thing, once we’ve got that collaboration, is to somehow record that in a way that is meaningful to anybody reviewing it, who might come around and look at it later, who might want to comment on it. Typically, that gets done using a ubiquitous language. People often use the ‘Given’, ‘When’, ‘Then’ words but that’s not necessary. The idea is that we’ve collaborated and this is shared understanding. This has made sure there is a collaborative goal that we’re trying to achieve and once we’ve got good at collaborating, it’s worth trying to capture that so that not everybody needs to be in the room at the same time, so that that shared learning can be propagated.

Finally, if it’s appropriate to our teams and to our projects, we automate our tests to drive the behaviour.

We collaborate, we record that collaboration in some form of specification, and then we automate that specification to drive out the implementation.

Cucumber isn't BDD

Matt and I both work for Cucumber Ltd but in his definition there is no mention of Cucumber anywhere. Cucumber is not part of BDD. Cucumber is something that has been created to help people automate in a specific way. If I go back to Nat and Steve’s book they just use JUnit throughout their book to automate acceptance tests. It depends entirely on your organization – how you want to practise BDD.

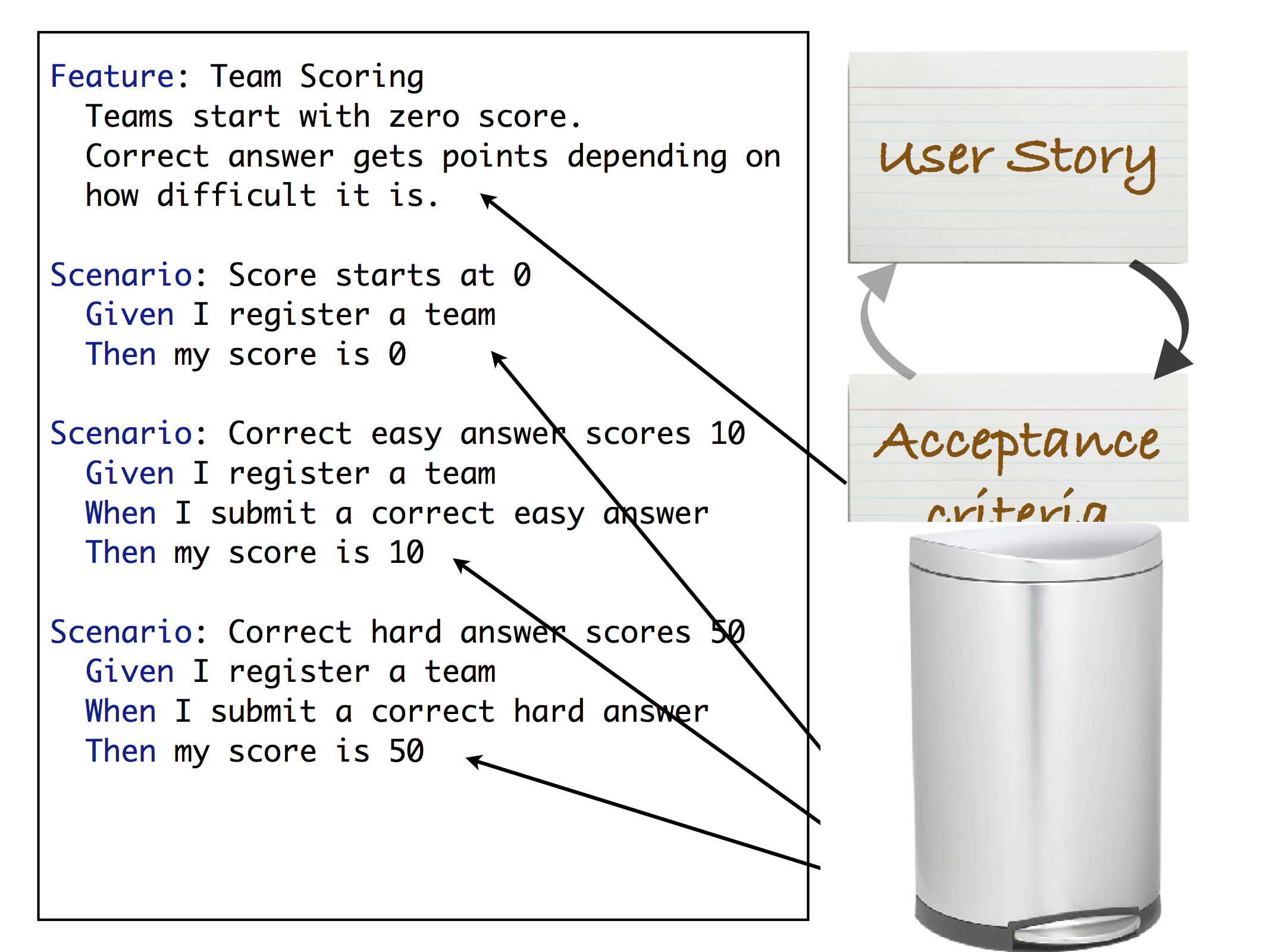

The classic way, using Cucumber and SpecFlow and any other tool that uses a semi-structured syntax called Gherkin, is to record and define those specifications. You eventually end up with what are called feature files.

Feature files are just plain text files. They have a semi-structure, there is a syntax, and the keywords are in blue. The intent is that anyone from your domain should be able to read your feature files and understand exactly what the intent is of the system.

Above is an example of a feature file. It has a name at the top saying what the feature is, it’s got some text which tells you what the behaviour or the acceptance criteria is and below it has a number of scenarios that show how the system behaves given certain situations. The important thing here is that the examples that you might come up with when you’re collaborating get recorded as the scenarios. The acceptance criteria, which are the rules, the way the system should be behaving are captured in the text at the top and the important thing here is that user stories, which a lot of Agile teams get very hung up on, are just rubbish at the end of the implementation and should be bent.

TDD and BDD: differences and contradictions

Moving on to the contradiction. We’ve explained both BDD and TDD. People often say ‘well, what’s the difference between them?’.

People also go on and ask ‘I’ve also heard about Acceptance Test-Driven Development (ATDD). What are they all? When should I use them? Are they different?’. The reality is that you can find websites that will tell you when to use which and in which environment. Liz Keogh who works with Dan North who invented the term BDD was asked this question – what’s the difference between all these things?

Her answer is ‘they’re just called different things’.

There is no essential difference between them. What holds them together is that they all require a group of people, specifying how the software should behave, collaboratively, before implementing it. That’s the important bit, so maybe that’s what we should boil the BDD definition down to. The idea is to work from the outside, thinking about how we want to pave, we use examples to make sure that everybody on the team understands what we’ve just agreed on – concrete examples with concrete data – and we write these examples in a ubiquitous language – a language using terms that derive from the business domain that are understood, unambiguously, by everybody on the team.

Design your tests - xDD

The "xDD" question. What is it all about? The reason it’s called ‘Test-Driven’ or ‘Behaviour-Driven’ or ‘Acceptance Test-Driven’ is that you have to specify the behaviour before you do the implementation. There is no ‘we sort of do Behaviour-Driven’, ‘we sort of do Test-Driven’, ‘we write the tests in the same sprint’. You have to write them first. That’s what drives them, that’s how it becomes a design process. It’s the failing specification, it’s the fact that you see it fail, which is driving you to do the implementation. That’s what pushes the developer; that’s what the developer uses to write the code.

The second D is for ‘design’ quite often. I know that it isn’t for ‘design’, it’s for ‘development’ but actually we’re designing code. When we write automation, we have to think about how it's going to be consumed, how are we going to invoke this method, how are we going to kick off this behaviour. By writing your code in response to your tests and listening to what that tells you, you get testability baked in, you get code that is testable, code you understand. You get a vast number of benefits way beyond test coverage.

It’s not about test coverage.

Finally, the refactoring that you get from both BDD and TDD is that you can now refactor until it feels good. People go ‘well, it would be nice if we knew when we’d refactor them’. Software is not ‘put the specs in the top, crank a handle and the right solution comes out’.

It’s a creative activity and as much as I’m sure you hate being thought as a creative, you are a creative. You have to have a feeling about it.

Conclusions

BDD, TDD, ATDD, Specification by Example – they’re all the same. They work from the outside in, they use examples to specify how the system should behave, those examples are then expressed in a ubiquitous language that the whole team understands, including the non-technical members, and then, once you’ve automated it, you get verification, which means that you can tell when your documentation is up to date, it means that you know when a regression has crept in, it means you can see how much of the system has been implemented by the development team.

All of these things are good.

But the relevant question when deciding whether to implement a test is this: Who is interested in reading these tests?

If you want some feedback from your business about something, if it’s a piece of behaviour that is really important to your product and your business is going to say ‘no, it shouldn’t work like that’, ‘yes, it should work like this’, really consider writing those tests in a way that they can read those tests and go ‘that is what we wanted’. Cucumber, SpecFlow, tools that use Gherkin allow you to do that directly in the ubiquitous language. However, you still don’t need to use them, you can write out long sentences within the technical frame that you’re working on and that would generate that readable documentation that you can share with your business. You can do it in JUnit, you can do it in CPP Light, you can do it in any of those tools; that's not a problem.

What you do need to do is make sure that it’s expressed in a way you get the feedback from the people who are interested, the people who have got a stake.

This is an edited transcript of Seb Rose's recent presentation at ACCU conference. You can watch the 15 minute talk here.