This is the first in a series of articles that will take a look at user stories, what they're used for, and how they interact with a BDD approach to software development. You could say that this is a story about user stories. And like every other story, it's important to choose where to begin – because, contrary to the advice given in the Sound of Music, it's not always a good idea to "start at the very beginning".

What's the problem?

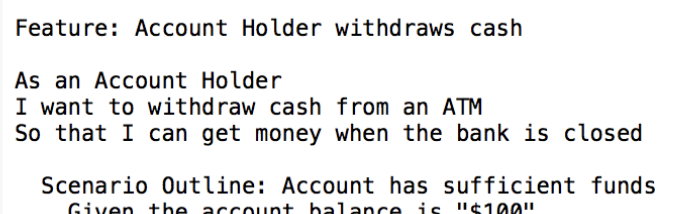

Several years ago, I gave a talk at CukenFest called Let Me Tell You A Story. It was inspired by a number of feature files that I'd seen online that started with text that looked remarkably like a user story.

Sample feature file

Sample feature file

This seemed very strange to me, because most features require the delivery of several user stories. So how could you choose just one one to put at the top of your feature file?

My colleague, Matt Wynne, believes the practice was encouraged by the original feature file snippet that shipped with TextMate many years ago when Cucumber was first gaining popularity.

Feature file snippet that ships with Sublime

Feature file snippet that ships with Sublime

Similar shortcuts also ship with Sublime Text and Visual Studio Code – and probably many other editors and IDEs.

The cargo cult effect has meant the majority of new Cucumber users who pick up these tools wrongly assume that putting their user story at the top of the feature file is the right thing to do.

The relationship between user stories and feature files is not well understood. This series of blogs aims to put that right.

Software development before agile

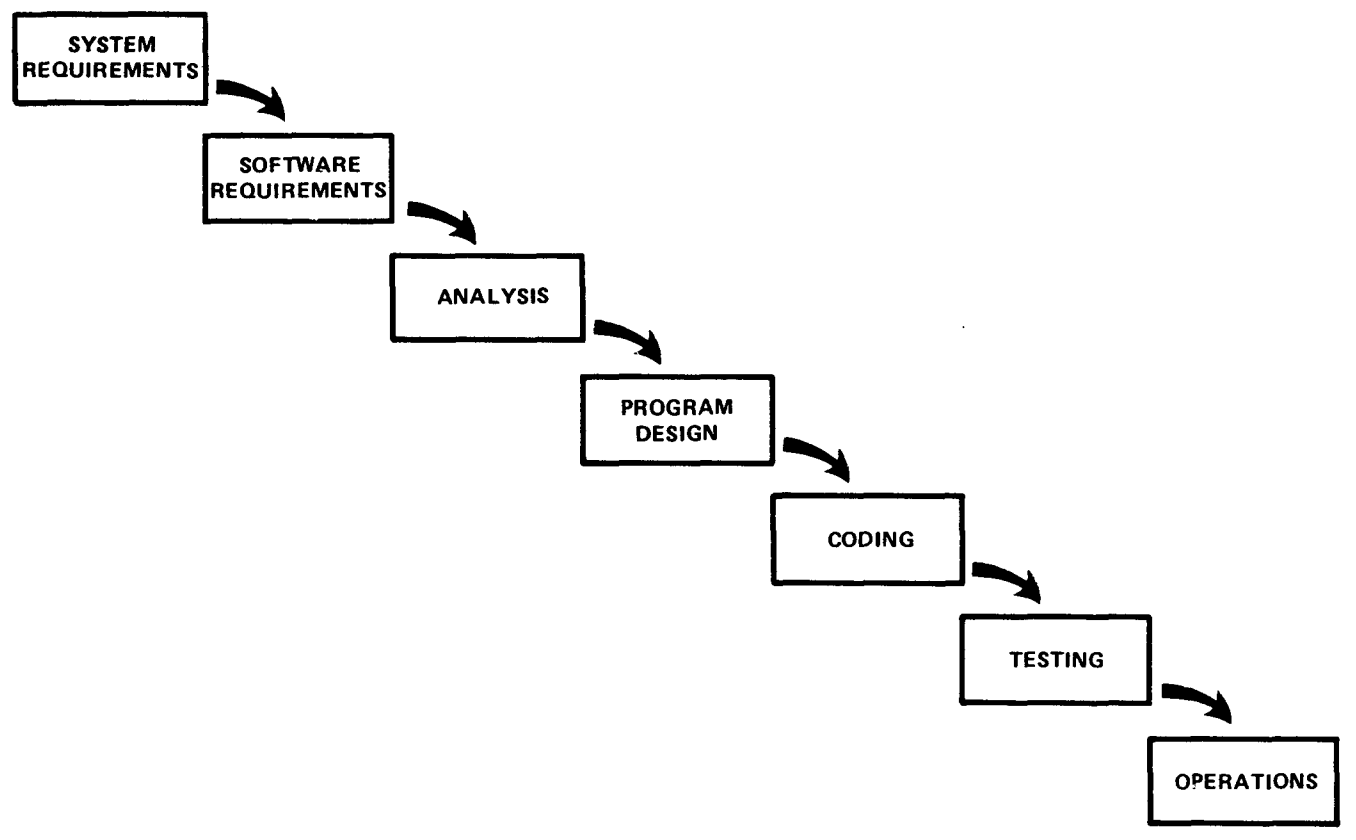

Let's take a journey back in time, to the 20th century. How did people develop software back in the dim, distant past, before the agile manifesto? The usual answer that people give is: "they used to use waterfall".

In the waterfall metaphor, software development is seen as a linear progression through various project stages: requirements analysis, architectural design, coding, testing, operations. The assumption is that work flows smoothly downhill – just like water.

The term waterfall was first used to describe this way of working in a 1976 paper by Bell & Thayer. The authors credited a 1970 paper by Winston Royce that never actually uses the word, waterfall. Not only that, but Royce's paper emphasises that this way of working "is risky and invites failure".

Even sadder, in 1985 — 15 years after Royce had warned about the risks — the US Department of Defence "captured this approach in DOD-STD-2167A, their standards for working with software development contractors."

It may surprise you to learn that even before Royce wrote his paper there were people who were working in a completely different way — using Iterative and Incremental Development (IDD). A paper written by Larman & Basili found traces of IID, that were "indistinguishable from XP", from as far back as 1958!

The problem with the waterfall approach is that at each stage people would spend weeks (or months) preparing detailed documents before passing them on to the team responsible for the next stage. Building software the same way you'd build a bridge or a skyscraper. It could be years before the first line of code was written, by which time requirements and priorities had often changed.

http://www-scf.usc.edu/~csci201/lectures/Lecture11/royce1970.pdf

http://www-scf.usc.edu/~csci201/lectures/Lecture11/royce1970.pdf

Most of the requirements that were discussed in detail were not delivered in the way that they had originally been envisaged. In fact, many never got delivered at all.

This was hugely wasteful, both in terms of the cost of delay, and the time spent analysing and specifying features that would never see the light of day.

The risks associated with waterfall development have been known about for a long time. Iterative and incremental approaches – that mitigate those risks – are not a recent development, though it's only recently that they've become mainstream.

What are stories for?

Fast forward a few decades, and we find a handful of experienced programmers determined to tackle the fact that the waterfall approach led to significant waste.

These consultants were breaking the mould, coming up with their own practices and methodologies aimed at minimising the waste inherent in spending time doing detailed design work prematurely. Instead, they suggested working in an incremental and iterative fashion, deferring detailed design work until it was clear that the functionality was about to be delivered. Collectively, these became known as lightweight methodologies.

One of these methodologies was called eXtreme Programming (XP).

The XP folk created the concept of a story as a "placeholder for a conversation". This allowed them to do high-level decomposition of the work that needed to be done (stories), while accepting that more detailed analysis (conversations) would be needed before implementation started.

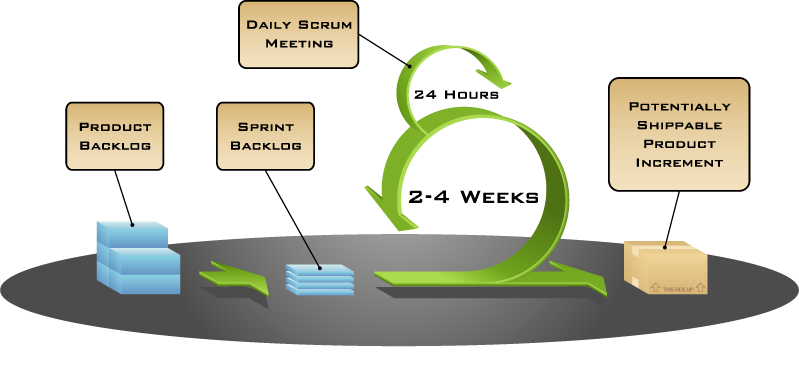

Another popular methodology at the time was Scrum. The Scrum Guide doesn't mention stories, but includes a concept that embraces them, called the Product Backlog Item (PBI). Each PBI represents some functionality that can be prioritised by the Product Owner. Scrum is not prescriptive about what format a PBI should take, although they are often represented as stories.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Scrum_diagram_(labelled).png

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Scrum_diagram_(labelled).png

A story is a way of remembering that a piece of work might need to be done, without committing to actually doing it, or diving into the details too soon.

Putting the 'user' into user story

Lightweight methodologies were a big hit, but there were so many of them that it was difficult for anyone to decide which one to use. This led in 2001 to a gathering of 17 men at a ski resort, which in turn led to the agile manifesto. It's been a very influential document, but many of the things that people associate with "agile" aren't mentioned in it at all. On the subject of stories, the manifesto is entirely silent. However, one of the twelve principles speaks to the problem stories aim to solve:

Simplicity--the art of maximizing the amount of work not done--is essential.

The original description of the Planning Game in Extreme Programming Explained does mention stories – but the book doesn't use the term user stories anywhere. So, where did the inclusion of the word user come from?

I asked on Twitter, and it seems that no one really knows - at least no one that's telling. Martijn Meijering dug into the internet archive and discovered that in a snapshot from 2002, story and user story were used interchangeably on the C2 wiki (which is where the XP community discussed things).

However it happened, calling them user stories emphasised that the goal is to "maximise the value of software produced by the team". As stories began to be used more widely, teams needed a strong steer to ensure they prioritised work that would deliver value to the user, and the term user story did just that.

However, the use of the word user has led to many arguments. Should every story be from the perspective of a user? What users does the system have? Is the system administrator a user? Is the support team? Are the developers? What about another system consuming your API?

It's called a user story to help people focus on maximising the value of what's produced – but we must remember that value comes in many shapes and sizes.

A template is born

The challenges teams had writing user stories led to the creation of the Connextra template by Rachel Davies in the early 2000s. She found that it wasn't enough to just write the story from the user's perspective. Her teams seemed to have better conversations when the story contained three specific pieces of information:

- The feature that needs to be discussed

- The role that will get the benefit from the feature

- The benefit that is expected

https://twitter.com/rachelcdavies/status/1186313143611469826

https://twitter.com/rachelcdavies/status/1186313143611469826

Rachel's template is now almost universal, in part due to its inclusion by Mike Cohn in his seminal books Agile Estimating and Planning and User Stories Applied:

As a <type of user>

I want <capability>

so that <business value>

The template is guidance to help teams capture enough information in the story, so that the conversation they have is valuable.

Like any one-size-fits all system, while the template can be very useful for beginners, blind adherence to it can become problematic. Rachel herself describes some of the problems that treating this template as catechism can cause:

"... this format can lead people to focus more on end users interests rather than the perspective of the person putting the business case forward. Also when given a template people can start treating story cards written this way as mini-requirements specs focussing on the written words rather than using stories as tools for driving a conversation. Even worse, stories that don't fit this form will be battered into shape until they do."

Stories help you ask the right questions about the context and reason for the request. The important part is not about the words on the card but the shared understanding developed in the team.

Back to the future

Fast forward another couple of decades, and we find the user story as an almost universally recognised term in our industry's vocabulary. However, in practice, we see the understanding of the term varies widely from team to team, from organisation to organisation.

Even though stories were intended to defer detailed analysis until the functionality was about to be developed, this is often not how they are used. There are many teams that use electronic tracking software (e.g. Jira) to build backlogs that contain hundreds of stories, each concealing detailed requirements. And despite the original intent of a story as a placeholder for a conversation, these details have never been discussed with the team.

So, while the term user story is widely used, it can mean very different things depending on who you talk to. This series of posts aims to fix that.

Next time ...

In this post, I've given an overview of the evolution of the user story as it is commonly used today. Next time, I'll be digging into the BDD practice of Discovery, and the uncomfortable metamorphosis that stories undergo in the process.

Other references

Responsibility Driven Design - Rebecca Wirfs-Brock

A Laboratory for Teaching Object Oriented Thinking - Kent Beck, Ward Cunningham

Card, conversation, confirmation – Ron Jeffries.