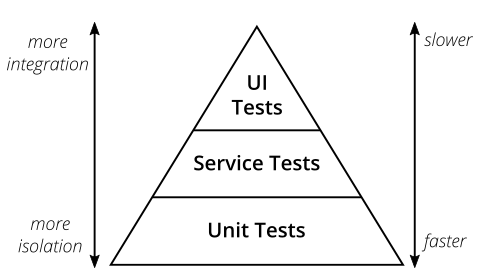

The Test Automation Pyramid was popularised by Mike Cohn in his book, Succeeding with Agile.

https://martinfowler.com/articles/practical-test-pyramid.html

Over the years it has been rendered in dozens of different ways.

It has been applied, misapplied, discussed, dismissed, and repurposed. Through all it’s many changes, it remains just as useful at starting heated discussions as it ever was. In this article I add fuel to the fire by revisiting the eviscerated triangle that I first published in 2015.

Metaphor

The Test Pyramid is a metaphor intended to suggest that the foundation of a test automation strategy should be large numbers of small, fast unit tests. As the automated tests become larger and slower, there should be fewer of them. That’s it. Period.

George Box is often quoted as having said “all models are wrong, but some are useful.” The pyramid is not a model. It’s not a framework. It’s not even a heuristic. It’s something much weaker than that -- it’s a metaphor.

However, it does conform to George Box’s aphorism in one important respect -- it is wrong!

It’s not a pyramid, it’s a triangle.

At XP2016 we tried to put the matter to rest with a park bench panel discussion: Does the Test Automation Pyramid matter and who really cares? We had many luminaries contribute to the discussion, including David Evans, Elisabeth Hendrickson, John Fergusson Smart, Simon Brown, Steve Freeman, and Bob Martin. The discussion generated a few laughs and a lot more heat than light. There was no consensus.

So, if the experts can’t agree, is there any value left in this broken, contentious metaphor?

Labels

Apart from the pyramid/triangle confusion, the main sticking point with the metaphor has been the labels that have been placed within it -- and the lines between them. Over the years this metaphor has been repurposed from many different viewpoints and the labels have varied significantly.

Despite the huge choice of pyramids to dicuss, I'm going to focus on the original labels that Mike Cohn used and explain why I find them problematic.

Let’s start at the bottom and the label “Unit tests.” This is a term that is widely used, but there is no consensus about what a unit test actually is. Michael Feathers, author of Working Effectively With Legacy Code, agrees that there is no definition of unit test and instead offers a list of indicators that you shouldn't find in a unit test.

A test is not a unit test if:

I sometimes try to get around this problem by talking about “programmer tests”, but while that solves the lack of definition, it doesn’t help in the context of the pyramid metaphor -- because programmers write tests at every level of the pyramid.

In the middle, Mike has the label “Service Tests.” He gives a lengthy description of what he means by this in one of his blog posts, where he laments that no one remembers to write service tests. The trouble is that there’s no agreement about where a unit ends and a service begins. In his popular conference rant, Ian Cooper claims to channel Kent Beck’s original idea that a unit test should exercise the behaviour of a public API rather than low level implementation details, such as a class. That sounds a lot like a service test to me.

Is “UI Test” any clearer as a label? If anything, I’d suggest that this is the most misleading of all. Do you really want to test your UI at the top of the pyramid, with the whole of your system connected to it? I would far prefer to test the UI in isolation, at the bottom of the pyramid. We will want a few tests that exercise the whole application, but that shouldn’t be how we check all the myriad behaviours that a UI exhibits.

It should be clear by now that there is no clean separation between the three labelled segments of the pyramid. Unfortunately, not everyone understands this and I’ve seen organisations attempt to gather statistics about what proportion of tests being created fall into each category. Worse, they have set acceptable values that they have “derived” from the pyramid and have attempted to enforce them through automated build rules. Never has Goodhart’s law been more clearly demonstrated: "When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure."

Can we rescue the metaphor? I believe so.

Eviscerated

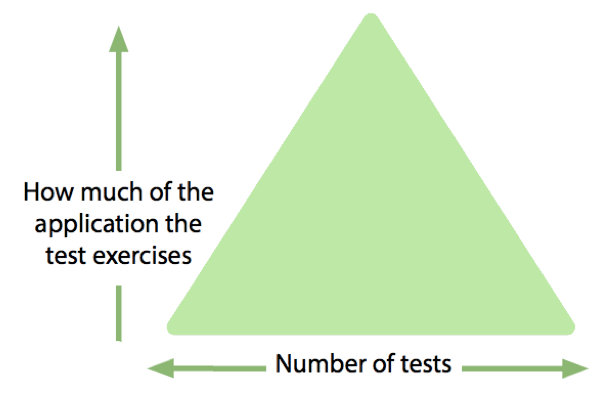

Ham Vocke summarises the purpose of the test automation pyramid thus:

Your best bet is to remember two things from Cohn's original test pyramid:

- Write tests with different granularity

- The more high-level you get the fewer tests you should have

And, at the end of the XP2016 discussion I mentioned earlier, Paul Rohorzka shared this insight (paraphrased by me) : “[the] vertical axis of pyramid represents pain over feedback"

I believe that both of the excerpts above are embodied in my eviscerated version of the triangle which I created during a discussion with Simon Brown.

What this tells us is that most tests should exercise as little of the application as they can. These tests should document the behaviour and validate the correctness of small amounts of code.

As we move up the triangle, we will write fewer tests, but they will exercise progressively more of the application. At the same time, the intent of the tests changes to documenting the interaction between components, the messages they pass between each other, and the protocols that they use. This includes behaviours such as validation and error handling.

When we reach the top of the triangle we are exercising the whole application. We should already have confidence that each component behaves as intended. We should also have confidence that each interaction between components has been exercised to verify that both ends of the dependency have the same understanding of the protocol that they share. All that remains is to verify that “the system hangs together.” These are sometimes characterised as smoke tests, and they check that the application has been deployed successfully and correctly configured for that specific environment.

Another important consideration as you move up the triangle has been succintly described by Beth Skurrie:

"... the more code the test covers, the lighter the touch of the test should be ... it's easy to fall into the trap of asserting more the more code a test covers, when it's much more maintainable to be asserting less, or at least, making more flexible assertions."

Although not part of the metaphor, I can't help but mention the following properties that I find useful when writing and curating tests:

- Understandable

- Maintainable

- Repeatable

- Necessary

- Granular

- Fast

All tests should exhibit the first four properties in this list. As you move up the the triangle, the last two properties (granular and fast) become less achievable.

Conclusion

The test automation pyramid has been a useful metaphor over many years, but it is open to much misinterpretation. The eviscerated triangle says less and so has less room for misinterpretation. I have found it useful as a training device and as a practical touchstone when thinking about what tests to write.

Will this article extinguish the fires of discord? I doubt it, but I’d love to hear your opinions -- whether you vehemently agree or emphatically disagree.