The original version of this post was published on Medium by The BDD Advocate.

The full spectrum of Behaviour Driven Development involves collaborative activities at both a high level, e.g. discovery workshops, and at a lower level — in terms of automating the discovered use-cases.

The discovery however, is sometimes the hardest part, making sure all the use-cases of the system are known and understood by all concerned: from the product owners, who know how the product should work, to the programmers who need to build the system to these precise specifications.

There are several collaborative techniques for facilitating group activities that lead to a clearer understanding of the system, but knowing where to start is always challenging. I have found that, by collaboratively building a timeline, one is forced to gradually cover the whole scope of the system’s behaviour, and through which it becomes clear to everyone what the essential and/or most complex features of the system are.

I’ve decided to call this particular technique “Event Mapping”, in reference to two popular methods of collaboratively understanding software requirements. In both of these approaches, technical people should work alongside product people, with the aim of communicating as clearly as possible and developing a shared understanding.

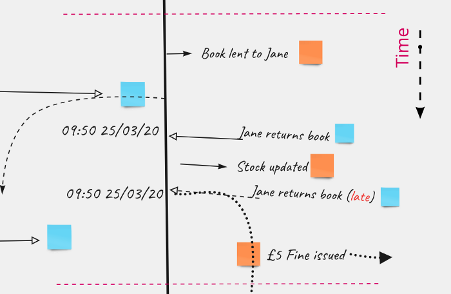

The first is Event Storming, a highly collaborative technique for sketching out the timeline of a system (for either existing or future requirements) in terms of system-commands and system-events (which makes this technique very well suited to event-driven systems). Event Storming, a term coined by Alberto Brandolini, requires participants to write down system events that are of interest to the business on post-it notes and place them on a long sheet of paper that represents a timeline. This activity eventually delineates the system in terms of significant events that happen throughout its lifetime (e.g. “Order Was Dispatched”) and the commands which cause them (e.g. “Place Order for Items”).

In this way, the whole group effectively visualises what happens when and why. In this way it becomes easy to see and discuss both the logic and the order in which things are supposed to happen.

Example Mapping, another collaborative technique invented by Matt Wynne, focuses on deriving use-cases or scenarios from business rules. The output of an Example Mapping session is a set of clear-cut examples of how of a user would use the required system; the examples must be concrete enough to be translated into executable specifications (e.g. gherkin). For example, each “feature”, or “capability” of the system is focused on in turn. The business rules are clearly spelt out (for example “members are fined £5 if a book is returned late”) and these examples are teased-out collectively by the product owner and the team.

Each example is written down on sticky note and placed below the rule they illustrate. The examples should be as concrete as necessary to remove ambiguity from the rule that they are illustrating. Imagine we had a rule that says books can only be taken out for 2 days, otherwise a fine is issued. A relevant example used to illustrate this rule might be: “Jon attempts to return a book he took out 3 days ago”

From these, gherkin scenarios can then be easily written down or scenarios picked as candidates for automation.

A Gherkin scenario is basically a micro-timeline

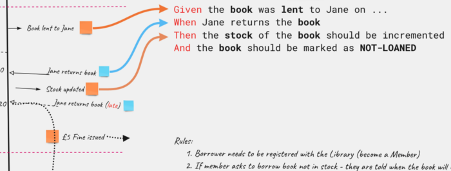

To recap: Using the Gherkin format of Given/When/Then for describing system use-cases is simply a way of making the three stages of a test explicit. Every test for a dynamic system has three phases:

- Set-up the system in a known state, which it needs to be in for the use-case to be tested — i.e what needs to have happened before (2)

- Take the action to test / Carry out the use-case on the system

- Check that the expected outcome happened — as a result of playing out the use-case.

As a colleague of mine pointed out, after he’d taken part in a few Event Storming workshops: When you’ve got all the events and commands lined up in temporal order — it becomes trivial to write Given/When/Then scenarios.

The reason for this is of course that the sequence Event-Command-Event maps directly to Given/When/Then. Indeed, when modelling an event-driven system, things become even simpler: The implementation of the Given step are the relevant events that happen directly before the command we want to test. The When step is simply the command we give the system, and the Then step checks that the expected events were emitted as a result of executing the command. Considered in this way, scenarios are essentially micro-timelines.

In order to extract use-cases, we only need to look for the commands — plus the events that directly precede and follow it. The process for this is no different for an event-driven system than it is for a synchronous API based system.

Example Use Case — Library Lending System

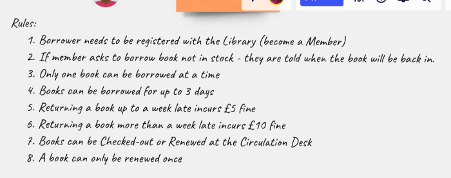

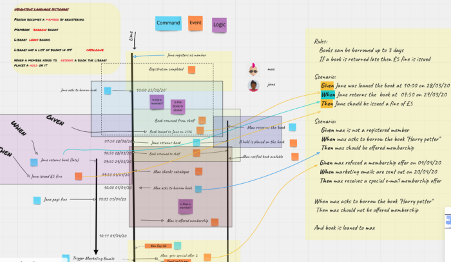

The “business rules” are simply the rules by which the business operates. For each rule, we need to come up with an example (how the rule is used). They can be written down at the same time as coming up with the events in the timeline. Depending on the rule, an alternate timeline might split off from the main one.

Event Mapping

By sketching the events that happen in the system on to a downward-facing timeline, we can build up a mapping from events and commands directly to Gherkin scenarios. I’d encourage not thinking about the distinction between events and commands but rather just sketch-out “significant things” that happen over time. It will become quickly clear which are events and which are commands. The latter are, in-effect, how the user interacts with the system. For example, if the user is a library member, a command they might issue to the system would be “Return Book X”

It is helpful to then use the two colours traditionally assigned to events and commands in order to separate them visually (orange and blue, respectively). This assists greatly in identifying scenarios and extracting them into a Given/When/Then formulation. I’ve used Miro boards, which is a great tool for remote collaboration, and it’s nice for anchoring the event/command/event arrows to given/when/then (they “stick” together when moved around).

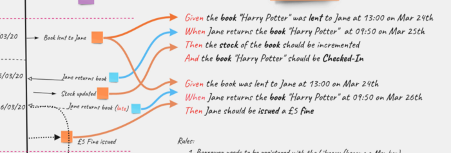

As with example mapping, the resulting scenarios each illustrate one of the rules shown above: For example, we might have

- An orange event sticky saying “Jon borrowed the book on the 21st Oct” (this could be event is dispatched on the 21st Oct.)

- A blue command sticky saying “Jon returns the book on the 28th of Oct” (the command is sent to the system on this date)

- A second orange event stick follows it saying “Jon is issued a £10 fine” (date here is irrelevant to this scenario)

This triad would together form the scenario: Returning a book late results in a £10 fine

Given: “Jon” borrowed the book at 12pm on the 21st Oct

When “Jon” returns the book at 12pm on the 28th of Oct

Then “Jon” should be issued a £10 fine

The scenarios are then excellent candidates for automation using tools such as Cucumber or Behat.

Alternately, we could consider automating the actual timeline — rather than use Gherkin. Given the Advanced API Miro-Boards provide, this is technically feasible. (Worth noting here that executable specifications don’t have to be written in Gherkin. The behavioural expectations of the system don’t have to be expressed in words, they can also be expressed in graphs or even pictorial examples — see Approval Testing tools)

As the number of scenarios grows, the ubiquitous language of the domain (see DDD) will gradually come into sharper focus. Which book was loaned? At what time? So you say that a member “reserves a book” but that the Library “puts a book on hold”?

As scenarios of a temporal nature are added, such as “What happens when a book is returned late?”, the times are added to the scenarios. It’s very useful, in such cases, to have a timeline right next to the scenarios themselves.

The timeline should be detailed enough to contain the precise times of borrowing and returning, and the scenarios should merely have to copy details of those specific interactions.

For alternate timelines (Jane returns the book late) I draw a parallel timeline which splits off from the main timeline. Events that happen on this timeline effectively become separate scenarios (e.g. the one where Jane is fined).

Finally, we can use different ways to mark or identify different scenarios. Here’s a screenshot from a session I ran at the last Cukenfest. I later identified the use-cases that can be mapped to scenarios and marked them using different coloured rectangles.

Jon Acker, Senior Consulting Engineer at Armakuni, London